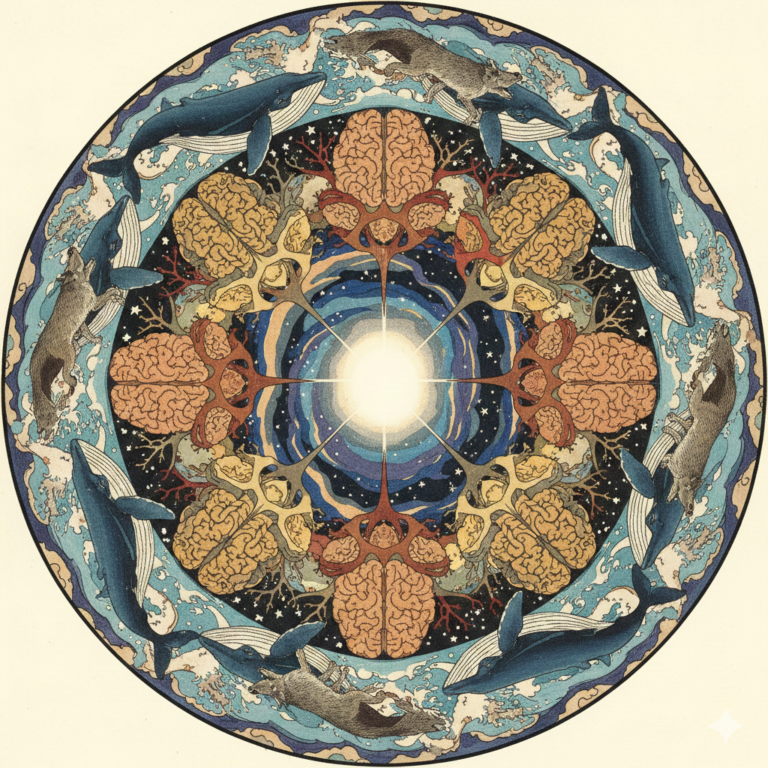

Congratulations to Anil Seth for winning the Berggruen essay prize on consciousness! I didn’t learn the outcome until I emerged from one of the rare cellular blackout zones in modern America. My wife and I were whale watching south of Yachats (“ya-hots”) on the Oregon coast in this week of remarkable weather. We came up bupkis, nada, nil for the great migratory grays, but saw seals and sea lions bobbing in the surf, red shouldered hawks, and one bald eagle glowering like a luminescent gargoyle atop a Sitka spruce near Highway 101. We turned around at the dune groupings by Florence (Frank Herbert’s inspirations for Dune, weirdly enough, where thinking machines have been banned) and headed north again, the intestinal windings of the roads causing us to swap our sunglasses in and out in synchrony with the center console of the car as it tried to understand the intermittent shadows.

Seth is always reliable and his essay continues themes he has recently written about. There is a broad distrust of computational functionalism and hints of alternative models for how consciousness might arise in uniquely biological ways like his example of how certain neurons might fire purely for regulatory reasons. There are unanswered questions about whether LLMs can become conscious that hint at the challenges such ideas have, and the moral consequences that manifold conscious machines entail. He even briefly dives into the Simulation Hypothesis and its consequences for the possibility of consciousness.

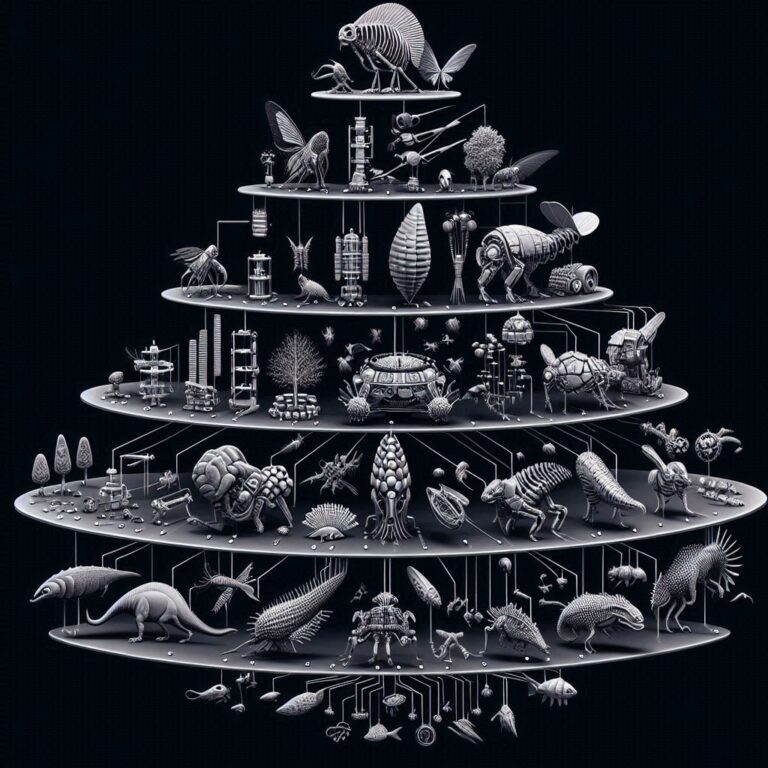

I’ve included my own entry, below. It is both boldly radical and also fairly mundane. I argue that functionalism has a deeper meaning in biological systems than as a mere analog of computation. A missing component of philosophical arguments about function and consciousness is found in the way evolution operates in exquisite detail, from the role of parasitism to hidden estrus, and from parental investment to ethical consequentialism.… Read the rest