In addition to Cormac McCarthy, Milan Kundera died this summer after a remarkable run of 94 years. I first read The Unbearable Lightness of Being in the early 90s and loved the strange detachment of the narrator and small moments like the critique of muzak in restaurant settings (I am now much more critical of restaurants that poorly manage sound reflections; how am I to enjoy my company in a cacophony?) But I had little use for his central philosophical pretense concerning eternal return or the use of metaphors as placeholders for people, though I have known people who strain to operate that way. Structuring a narrative around flimsy Continental ideas from Nietzsche, in turn influenced by Hinduism, Buddhism, and even Pythagoras, was too conspicuously self-absorbed with an intellectual airiness. It’s easy to achieve pretension but quite another thing to convey lofty thoughts effortlessly. I might have accepted a narrator musing on the topic among many others, playing with it while laughing at his own ridiculousness, and concluding that such concepts were mythological at best.

In addition to Cormac McCarthy, Milan Kundera died this summer after a remarkable run of 94 years. I first read The Unbearable Lightness of Being in the early 90s and loved the strange detachment of the narrator and small moments like the critique of muzak in restaurant settings (I am now much more critical of restaurants that poorly manage sound reflections; how am I to enjoy my company in a cacophony?) But I had little use for his central philosophical pretense concerning eternal return or the use of metaphors as placeholders for people, though I have known people who strain to operate that way. Structuring a narrative around flimsy Continental ideas from Nietzsche, in turn influenced by Hinduism, Buddhism, and even Pythagoras, was too conspicuously self-absorbed with an intellectual airiness. It’s easy to achieve pretension but quite another thing to convey lofty thoughts effortlessly. I might have accepted a narrator musing on the topic among many others, playing with it while laughing at his own ridiculousness, and concluding that such concepts were mythological at best.

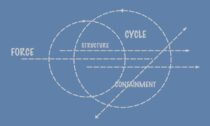

But there is a certain circularity in that otherwise educated people continue to latch onto narratives and metaphors that are appealing and unexpectedly strange, from little dioramas about the motives of people in our lives to grand conspiracies and mythologies filled with resurrections, demons, and eschatologies. The conspiracy narratives are a special contemporary problem accelerated by modern communications technologies, but there is nothing particularly new about them in thrust, focus, or pervasiveness.

Aluminum cans cause Alzheimer’s disease? Procter and Gamble’s logo was satanic? When I was in the Peace Corps in Fiji, the Hindu kids thought that certain toothpastes from Australia were adulterated with cow fat or something to undermine Hinduism.… Read the rest