Sitting at JFK reading Scholarpedia’s comprehensive entry on Recurrent Neural Networks, waiting for my flight to Iceland with my kid while the sun drops just to the north of Freedom Tower…priceless.… Read the rest

Sitting at JFK reading Scholarpedia’s comprehensive entry on Recurrent Neural Networks, waiting for my flight to Iceland with my kid while the sun drops just to the north of Freedom Tower…priceless.… Read the rest

Category: Cognitive Science

Evolutionary Optimization and Environmental Coupling

Carl Schulman and Nick Bostrom argue about anthropic principles in “How Hard is Artificial Intelligence? Evolutionary Arguments and Selection Effects” (Journal of Consciousness Studies, 2012, 19:7-8), focusing on specific models for how the assumption of human-level intelligence should be easy to automate are built upon a foundation of assumptions of what easy means because of observational bias (we assume we are intelligent, so the observation of intelligence seems likely).

Carl Schulman and Nick Bostrom argue about anthropic principles in “How Hard is Artificial Intelligence? Evolutionary Arguments and Selection Effects” (Journal of Consciousness Studies, 2012, 19:7-8), focusing on specific models for how the assumption of human-level intelligence should be easy to automate are built upon a foundation of assumptions of what easy means because of observational bias (we assume we are intelligent, so the observation of intelligence seems likely).

Yet the analysis of this presumption is blocked by a prior consideration: given that we are intelligent, we should be able to achieve artificial, simulated intelligence. If this is not, in fact, true, then the utility of determining whether the assumption of our own intelligence being highly probable is warranted becomes irrelevant because we may not be able to demonstrate that artificial intelligence is achievable anyway. About this, the authors are dismissive concerning any requirement for simulating the environment that is a prerequisite for organismal and species optimization against that environment:

In the limiting case, if complete microphysical accuracy were insisted upon, the computational requirements would balloon to utterly infeasible proportions. However, such extreme pessimism seems unlikely to be well founded; it seems unlikely that the best environment for evolving intelligence is one that mimics nature as closely as possible. It is, on the contrary, plausible that it would be more efficient to use an artificial selection environment, one quite unlike that of our ancestors, an environment specifically designed to promote adaptations that increase the type of intelligence we are seeking to evolve (say, abstract reasoning and general problem-solving skills as opposed to maximally fast instinctual reactions or a highly optimized visual system).

Why is this “unlikely”? The argument is that there are classes of mental function that can be compartmentalized away from the broader, known evolutionary provocateurs.… Read the rest

Active Deep Learning

Deep Learning methods that use auto-associative neural networks to pre-train (with bottlenecking methods to ensure generalization) have recently been shown to perform as well and even better than human beings at certain tasks like image categorization. But what is missing from the proposed methods? There seem to be a range of challenges that revolve around temporal novelty and sequential activation/classification problems like those that occur in natural language understanding. The most recent achievements are more oriented around relatively static data presentations.

Deep Learning methods that use auto-associative neural networks to pre-train (with bottlenecking methods to ensure generalization) have recently been shown to perform as well and even better than human beings at certain tasks like image categorization. But what is missing from the proposed methods? There seem to be a range of challenges that revolve around temporal novelty and sequential activation/classification problems like those that occur in natural language understanding. The most recent achievements are more oriented around relatively static data presentations.

Jürgen Schmidhuber revisits the history of connectionist research (dating to the 1800s!) in his October 2014 technical report, Deep Learning in Neural Networks: An Overview. This is one comprehensive effort at documenting the history of this reinvigorated area of AI research. What is old is new again, enhanced by achievements in computing that allow for larger and larger scale simulation.

The conclusions section has an interesting suggestion: what is missing so far is the sensorimotor activity loop that allows for the active interrogation of the data source. Human vision roams over images while DL systems ingest the entire scene. And the real neural systems have energy constraints that lead to suppression of neural function away from the active neural clusters.

The Deep Computing Lessons of Apollo

With the arrival of the Apollo 11 mission’s 45th anniversary, and occasional planning and dreaming about a manned mission to Mars, the role of information technology comes again into focus. The next great mission will include a phalanx of computing resources, sensors, radars, hyper spectral cameras, laser rangefinders, and information fusion visualization and analysis tools to knit together everything needed for the astronauts to succeed. Some of these capabilities will be autonomous, predictive, and knowledgable.

With the arrival of the Apollo 11 mission’s 45th anniversary, and occasional planning and dreaming about a manned mission to Mars, the role of information technology comes again into focus. The next great mission will include a phalanx of computing resources, sensors, radars, hyper spectral cameras, laser rangefinders, and information fusion visualization and analysis tools to knit together everything needed for the astronauts to succeed. Some of these capabilities will be autonomous, predictive, and knowledgable.

But it all began with the Apollo Guidance Computer or AGC, the rather sophisticated for-its-time computer that ran the trigonometric and vector calculations for the original moonshot. The AGC was startlingly simple in many ways, made up exclusively of NOR gates to implement Arithmetic Logic Unit-like functionality, shifts, and register opcodes combined with core memory (tiny ferromagnetic loops) in both RAM and ROM forms (the latter hand-woven by graduate students).

Using NOR gates to create the entire logic of the central processing unit is guided by a few simple principles. A NOR gate combines both NOT and OR functionality together and has the following logical functionality:

[table id=1 /]

The NOT-OR logic can be read as “if INPUT1 or INPUT2 is set to 1, then the OUTPUT should be 1, but then take the logical inversion (NOT) of that”. And, amazingly, circuits built from NORs can create any Boolean logic. NOT A is just NOR(A,A), which you can see from the following table:

[table id=2 /]

AND and OR can similarly be constructed by layering NORs together. For Apollo, the use of just a single type of integrated circuit that packaged NORs into chips improved reliability.

This level of simplicity has another important theoretical result that bears on the transition from simple guidance systems to potentially intelligent technologies for future Mars missions: a single layer of Boolean functions can only compute simple things.… Read the rest

Trees of Lives

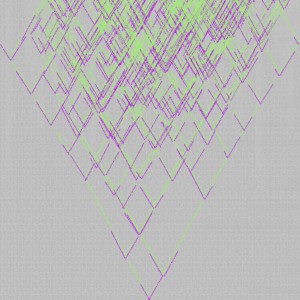

With a brief respite between vacationing in the canyons of Colorado and leaving tomorrow for Australia, I’ve open-sourced an eight-year-old computer program for converting one’s DNA sequences into an artistic rendering. The input to the program are the allelic patterns from standard DNA analysis services that use the Short Tandem Repeat Polymorphisms from forensic analysis, as well as poetry reflecting one’s ethnic heritage. The output is generative art: a tree that overlays the sequences with the poetry and a background rendered from the sequences.

With a brief respite between vacationing in the canyons of Colorado and leaving tomorrow for Australia, I’ve open-sourced an eight-year-old computer program for converting one’s DNA sequences into an artistic rendering. The input to the program are the allelic patterns from standard DNA analysis services that use the Short Tandem Repeat Polymorphisms from forensic analysis, as well as poetry reflecting one’s ethnic heritage. The output is generative art: a tree that overlays the sequences with the poetry and a background rendered from the sequences.

Generative art is perhaps one of the greatest aesthetic achievements of the late 20th Century. Generative art is, fundamentally, a recognition that the core of our humanity can be understood and converted into meaningful aesthetic products–it is the parallel of effective procedures in cognitive science, and developed in lock-step with the constructive efforts to reproduce and simulate human cognition.

To use Tree of Lives, install Java 1.8, unzip the package, and edit the supplied markconfig.txt to enter in your STRs and the allele variant numbers in sequence per line 15 of the configuration file. Lines 16+ are for lines of poetry that will be rendered on the limbs of the tree. Other configuration parameters can be discerned by examining com.treeoflives.CTreeConfig.java, and involve colors, paths, etc. Execute the program with:

java -cp treeoflives.jar:iText-4.2.0-com.itextpdf.jar com.treeoflives.CAlleleRenderer markconfig.txt… Read the rest

Inching Towards Shannon’s Oblivion

Following Bill Joy’s concerns over the future world of nanotechnology, biological engineering, and robotics in 2000’s Why the Future Doesn’t Need Us, it has become fashionable to worry over “existential threats” to humanity. Nuclear power and weapons used to be dreadful enough, and clearly remain in the top five, but these rapidly developing technologies, asteroids, and global climate change have joined Oppenheimer’s misquoted “destroyer of all things” in portending our doom. Here’s Max Tegmark, Stephen Hawking, and others in Huffington Post warning again about artificial intelligence:

Following Bill Joy’s concerns over the future world of nanotechnology, biological engineering, and robotics in 2000’s Why the Future Doesn’t Need Us, it has become fashionable to worry over “existential threats” to humanity. Nuclear power and weapons used to be dreadful enough, and clearly remain in the top five, but these rapidly developing technologies, asteroids, and global climate change have joined Oppenheimer’s misquoted “destroyer of all things” in portending our doom. Here’s Max Tegmark, Stephen Hawking, and others in Huffington Post warning again about artificial intelligence:

One can imagine such technology outsmarting financial markets, out-inventing human researchers, out-manipulating human leaders, and developing weapons we cannot even understand. Whereas the short-term impact of AI depends on who controls it, the long-term impact depends on whether it can be controlled at all.

I almost always begin my public talks on Big Data and intelligent systems with a presentation on industrial revolutions that progresses through Robert Gordon’s phases and then highlights Paul Krugman’s argument that Big Data and the intelligent systems improvements we are seeing potentially represent a next industrial revolution. I am usually less enthusiastic about the timeline than nonspecialists, but after giving a talk at PASS Business Analytics Friday in San Jose, I stuck around to listen in on a highly technical talk concerning statistical regularization and deep learning and I found myself enthused about the topic once again. Deep learning is using artificial neural networks to classify information, but is distinct from traditional ANNs in that the systems are pre-trained using auto-encoders to have a general knowledge about the data domain. To be clear, though, most of the problems that have been tackled are “subsymbolic” for image recognition and speech problems.… Read the rest

General AI with Jokes

Excerpts of Jürgen Schmidhuber’s talk on beauty, General AI, Gödel Machines, curiosity, and self-motivated rewards.… Read the rest

Parsimonious Portmanteaus

Meaning is a problem. We think we might know what something means but we keep being surprised by the facts, research, and logical difficulties that surround the notion of meaning. Putnam’s Representation and Reality runs through a few different ways of thinking about meaning, though without reaching any definitive conclusions beyond what meaning can’t be.

Meaning is a problem. We think we might know what something means but we keep being surprised by the facts, research, and logical difficulties that surround the notion of meaning. Putnam’s Representation and Reality runs through a few different ways of thinking about meaning, though without reaching any definitive conclusions beyond what meaning can’t be.

Children are a useful touchstone concerning meaning because we know that they acquire linguistic skills and consequently at least an operational understanding of meaning. And how they do so is rather interesting: first, presume that whole objects are the first topics for naming; next, assume that syntactic differences lead to semantic differences (“the dog” refers to the class of dogs while “Fido” refers to the instance); finally, prefer that linguistic differences point to semantic differences. Paul Bloom slices and dices the research in his Précis of How Children Learn the Meanings of Words, calling into question many core assumptions about the learning of words and meaning.

These preferences become useful if we want to try to formulate an algorithm that assigns meaning to objects or groups of objects. Probabilistic Latent Semantic Analysis, for example, assumes that words are signals from underlying probabilistic topic models and then derives those models by estimating all of the probabilities from the available signals. The outcome lacks labels, however: the “meaning” is expressed purely in terms of co-occurrences of terms. Reconciling an approach like PLSA with the observations about children’s meaning acquisition presents some difficulties. The process seems too slow, for example, which was always a complaint about connectionist architectures of artificial neural networks as well. As Bloom points out, kids don’t make many errors concerning meaning and when they do, they rapidly compensate.… Read the rest

In Like Flynn

The exceptionally interesting James Flynn explains the cognitive history of the past century and what it means in terms of human intelligence in this TED talk:

What does the future hold? While we might decry the “twitch” generation and their inundation by social media, gaming stimulation, and instant interpersonal engagement, the slowing observed in the Flynn Effect might be getting ready for another ramp-up over the next 100 years.

Perhaps most intriguing is the discussion of the ability to think in terms of hypotheticals as a a core component of ethical reasoning. Ethics is about gaming outcomes and also about empathizing with others. The influence of media as a delivery mechanism for narratives about others emerged just as those changes in cognitive capabilities were beginning to mature in the 20th Century. Widespread media had a compounding effect on the core abstract thinking capacity, and with the expansion of smartphones and informational flow, we may only have a few generations to go before the necessary ingredients for good ethical reasoning are widespread even in hard-to-reach areas of the world.… Read the rest

Contingency and Irreducibility

Thomas Nagel returns to defend his doubt concerning the completeness—if not the efficacy—of materialism in the explanation of mental phenomena in the New York Times. He quickly lays out the possibilities:

Thomas Nagel returns to defend his doubt concerning the completeness—if not the efficacy—of materialism in the explanation of mental phenomena in the New York Times. He quickly lays out the possibilities:

- Consciousness is an easy product of neurophysiological processes

- Consciousness is an illusion

- Consciousness is a fluke side-effect of other processes

- Consciousness is a divine property supervened on the physical world

Nagel arrives at a conclusion that all four are incorrect and that a naturalistic explanation is possible that isn’t “merely” (1), but that is at least (1), yet something more. I previously commented on the argument, here, but the refinement of the specifications requires a more targeted response.

Let’s call Nagel’s new perspective Theory 1+ for simplicity. What form might 1+ take on? For Nagel, the notion seems to be a combination of Chalmers-style qualia combined with a deep appreciation for the contingencies that factor into the personal evolution of individual consciousness. The latter is certainly redundant in that individuality must be absolutely tied to personal experiences and narratives.

We might be able to get some traction on this concept by looking to biological evolution, though “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” is about as close as we can get to the topic because any kind of evolutionary psychology must be looking for patterns that reinforce the interpretation of basic aspects of cognitive evolution (sex, reproduction, etc.) rather than explore the more numinous aspects of conscious development. So we might instead look for parallel theories that focus on the uniqueness of outcomes, that reify the temporal evolution without reference to controlling biology, and we get to ideas like uncomputability as a backstop. More specifically, we can explore ideas like computational irreducibility to support the development of Nagel’s new theory; insofar as the environment lapses towards weak predictability, a consciousness that self-observes, regulates, and builds many complex models and metamodels is superior to those that do not.… Read the rest