Meaning is a problem. We think we might know what something means but we keep being surprised by the facts, research, and logical difficulties that surround the notion of meaning. Putnam’s Representation and Reality runs through a few different ways of thinking about meaning, though without reaching any definitive conclusions beyond what meaning can’t be.

Meaning is a problem. We think we might know what something means but we keep being surprised by the facts, research, and logical difficulties that surround the notion of meaning. Putnam’s Representation and Reality runs through a few different ways of thinking about meaning, though without reaching any definitive conclusions beyond what meaning can’t be.

Children are a useful touchstone concerning meaning because we know that they acquire linguistic skills and consequently at least an operational understanding of meaning. And how they do so is rather interesting: first, presume that whole objects are the first topics for naming; next, assume that syntactic differences lead to semantic differences (“the dog” refers to the class of dogs while “Fido” refers to the instance); finally, prefer that linguistic differences point to semantic differences. Paul Bloom slices and dices the research in his Précis of How Children Learn the Meanings of Words, calling into question many core assumptions about the learning of words and meaning.

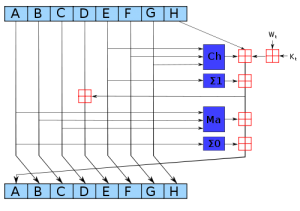

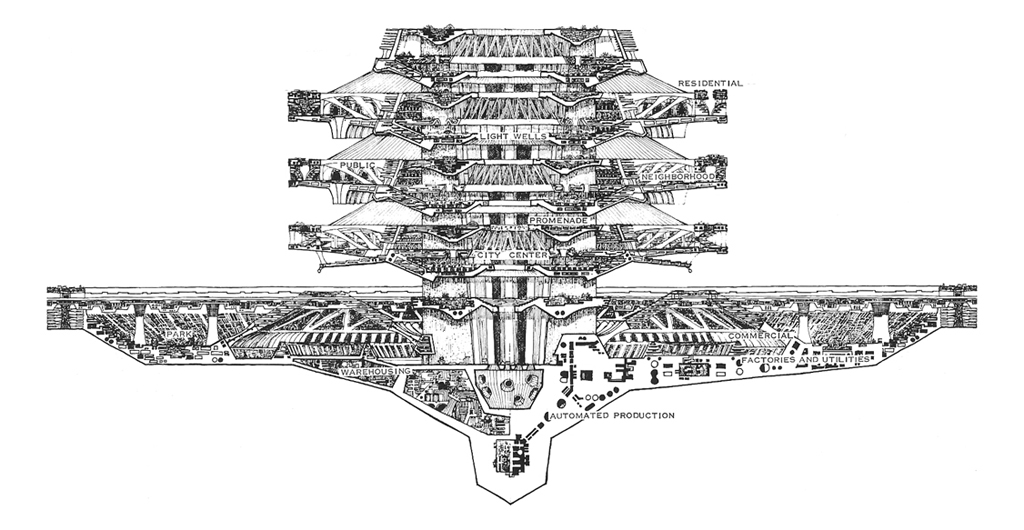

These preferences become useful if we want to try to formulate an algorithm that assigns meaning to objects or groups of objects. Probabilistic Latent Semantic Analysis, for example, assumes that words are signals from underlying probabilistic topic models and then derives those models by estimating all of the probabilities from the available signals. The outcome lacks labels, however: the “meaning” is expressed purely in terms of co-occurrences of terms. Reconciling an approach like PLSA with the observations about children’s meaning acquisition presents some difficulties. The process seems too slow, for example, which was always a complaint about connectionist architectures of artificial neural networks as well. As Bloom points out, kids don’t make many errors concerning meaning and when they do, they rapidly compensate.… Read the rest