Nasim Taleb’s 2nd Edition of The Black Swan argues—not unpersuasively—that rare, cataclysmic events dominate ordinary statistics. Indeed, he notes that almost all wealth accumulation is based on long-tail distributions where a small number of individuals reap unexpected rewards. The downsides are also equally challenging, where he notes that casinos lose money not in gambling where the statistics are governed by Gaussians (the house always wins), but instead when tigers attack, when workers sue, and when other external factors intervene.

Nasim Taleb’s 2nd Edition of The Black Swan argues—not unpersuasively—that rare, cataclysmic events dominate ordinary statistics. Indeed, he notes that almost all wealth accumulation is based on long-tail distributions where a small number of individuals reap unexpected rewards. The downsides are also equally challenging, where he notes that casinos lose money not in gambling where the statistics are governed by Gaussians (the house always wins), but instead when tigers attack, when workers sue, and when other external factors intervene.

Black Swan Theory adds an interesting challenge to modern inference theories like Algorithmic Information Theory (AIT) that anticipate predictability to the universe. Even variant coding approaches like Minimum Description Length theory modify the anticipatory model based on relatively smooth error functions rather than high “kurtosis” distributions of variable change. And for the most part, for the regular events of life and our sensoriums, that is adequate. It is only where we start to look at rare existential threats that we begin to worry about Black Swans and inference.

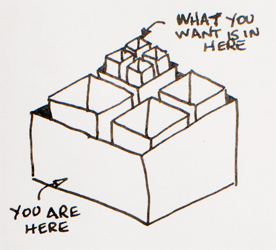

How might we modify the typical formulations of AIT and the trade-offs between model complexity and data to accommodate the exceedingly rare? Several approaches are possible. First, if we are combining a predictive model with a resource accumulation criteria, we can simply pad out the model memory by reducing kurtosis risk through additional resource accumulation; any downside is mitigated by the storing of nuts for a rainy day. Good strategy for moderately rare events like weather change, droughts and whatnot. But what about even rarer events like little ice ages and dinosaur extinction-level meteorite hits? An alternative strategy is to maintain sufficient diversity in the face of radical unknowns that coping becomes a species-level achievement.… Read the rest

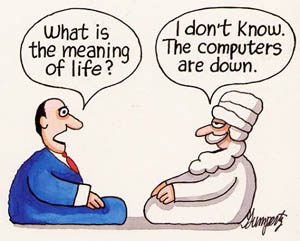

The impossibility of the Chinese Room has implications across the board for understanding what meaning means. Mark Walker’s paper “

The impossibility of the Chinese Room has implications across the board for understanding what meaning means. Mark Walker’s paper “