I love analytic philosophy. It’s like Seinfeld for ideas, a field with no particular content except the perplexing nature of ideas themselves. I’m reading Scott Soames’ attack on two-dimensional semantics right now, for instance. This has peculiar relevance in that insofar as meaning can be broken up into two dimensions there are ways of building modal logic justifications for things like “philosophical zombies” in the philosophy of mind. It’s a curious corner of this show about meaning and nothing more. I always fall back to Wittgenstein at some point: language is just games we play with one another. There are rules that we internalize and meaning has to do with the constraints those rules put on us. But, ahem, then we start asking what exactly are those rules and what kinds of internal logic helps to bind words and ideas together, so Wittgenstein is more of a deconstructive backstop that helps relieve us of the weight of expectation that there are mega-metatheories that can wrap all this meaning stuff up. Still, there remains the hard work to do that we see in linguistics and cognitive science where meaning representations and all the rules of these games are sketched out towards some kind of effective theory.

Another deconstructive reflection comes from the related concepts of Quine’s radical translation and Davidson’s radical interpretation. If we can’t ever really know with certainty what words mean to someone else then we need strategies to empirically probe, through questions and observations, and gradually develop a working theory about what the hell those other people are talking about. Meaning becomes science experiments. We test, we hypothesize, we have U-shaped curves, and we build up a tentative understanding.

I keep encountering cases where our entire human history is essentially a product of inexact translation, especially in the numinous universe of religious thinking. Our ancient ancestors dealt with day-to-day matters of great concreteness like people and animal names, navigating local and regional geographies, and acquiring food and raising families. But then they also concocted stories and imputed the universe with supernatural structures and causes. As they encountered others they acquired new spiritual ideas and gods and wove them into their own belief systems. We have fantastic words like syncretize, harmonize, monolatry, epithet, and apotheosis that reflect how these systems changed in the face of other ideas.

I particularly like the semantic challenges that impact Christian theology, like the appropriation of words from Germanic-Norse (Hell) and Greek (Hades, Tartarus) that were used to articulate a murky collection of ideas spread from Matthew through to Revelation. This has to be harmonized further with Old Testament terms like Sheol and Gehenna in complex theological undertakings in order to arrive at some kind of unified view of what these ancient people thought. More, all these gods and lesser supernatural beings get mashed up with other cultural names and epithets, from Lucifer to Lilith. The latter possibly being a complete mistranslation from Sumerian.

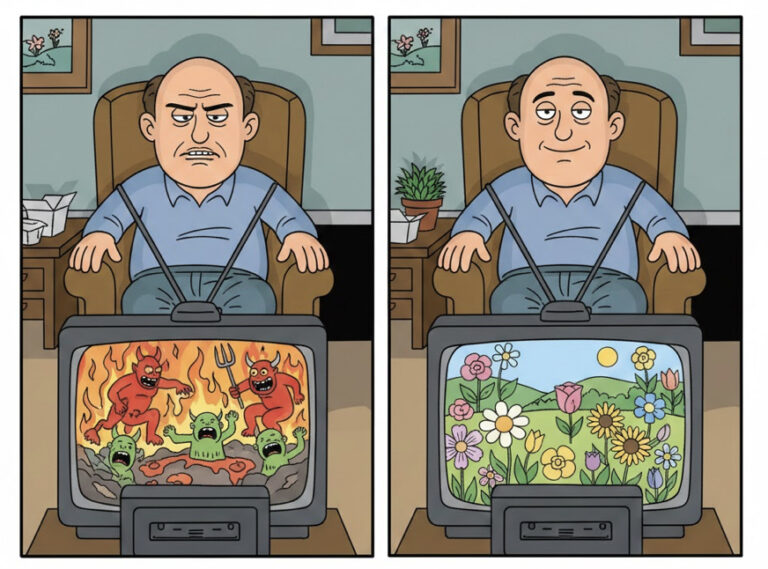

Yet all of this cyclonic borrowing and appropriation just became the mysterious scaffolding holding up day-to-day conceptions of a moral play that tries to optimize positive behavior, to keep us close to the tribe and synchronized. Sure, it’s murky whether you just die, get eternal torment, get burned up at judgment day (that maybe already happened?), achieve grace or the grave by acts or belief alone, and ultimately how this cosmic justice fulfills some kind of cosmic goal, but it has been enough to sustain elements of Western civilization for these last two millennia. We seem to be able to triangulate on enough of a story that the terms and their complex origins are not unduly distracting. The stories hold together and remain important cultural signposts.

In two-dimensional semantics the rigid reference of something like water is H20 but we can discuss water using the other dimension as something not yet fixed by scientific understanding. The logic of the statements we construct then operate on that secondary dimension of meaning. Many of these supernatural terms show something odder still. The only rigidity in reference was the first mention (in a causal semantic theory) but the meaning floated away from that pier almost immediately (who knows what the first Mycenaean guru in a cave really meant by “daimon”?) and keeps getting re-attached to different idea structures that are perhaps best described as being borne of some kind of evolution-like randomization and selective honing. They may stay close to the pier, combining and recombining with other notions, until they disappear over the horizon into some other metaphorical whirlwind (“the hell of war”).

But, paraphrasing George Castanza, the reason we are paying attention to this is because it’s in all these books, regardless of whether they are about something or not.

Fixed an UNDO corruption.