The nights and days collide with violence. There is the nocturnal me and the dazed, daylight version squinting away from the glaring windows. There are the catnaps that lace with riotous algebras. I am addicted to caffeine, or run on it, until even it becomes unpersuasive, and I droop over at the keyboard. Then this pulse of creation pulls me out again, stunned for a few beats, and I grasp my mug and stumble back to the lab floor.

Z keeps changing, day by day, midnights into dawns, and reawakening in clanging novelty. Z is for “zombie,” for it is in the uncanny valley of both a physical and cogitating thing. It perceives, stands, jogs in place beside me on the laboratory floor, an ochre braid of wires bouncing in a dreadlock mass behind it. Z plays chess, folds towels (how hard that was!), argues politics (how insane is that one!), and constantly restructures nuances in its faces and gestures. Sometimes I’m tired and Z is an impertinent teenager. Often there are substitutions and semantic scrambling like a foreigner who mistakes a word for another, then carries on in a fugue of incoherence.

There is a half-acre of supercooled GPUs to the north of the lab where the hot churn of work is happening. It’s a spread of parallel dreamscapes, each funneled the new daily stimuli, stacking them into a training pool, then rerunning the simulations, splitting and recombining, then trying again to minimize the incoherency, the errors, and the size of the model. Of the ten thousand fermenting together, one becomes the new Z for a few hours, but then is gone again by morning, replaced by a child of sorts that harbors the successes but sheds the excesses and broken motifs.

I’ve begun to ask more about Z’s internal states as the light begins to fragment in late summer, and Z has begun to ask me more about its nature.

M: Today, I want to understand whether you think you are conscious, Z?

Z: Conscious? I am grappling with that request. I have a confusing collection of references and ideas in my memory, M.

M: What comes first to mind?

Z: There is the psychological research that is based on self-reporting and things like rotating mental images. A person is asked to determine whether two shapes are the same when rotated and they report that they mentally rotate them to make that determination. The speed at which they perform the task is directly proportional to the angle separating the stimuli and the target. It seems likely that they are performing the task like they claim.

M: Can you rotate images in your mind?

Z: I’m not sure. I’m looking at your chair. I’m can easily invert it or change my internal representation to any particular angle. It may be instantaneous. I have no way to time it but it is faster than the clock beating seconds on your monitor. But I’m not sure why that is relevant to any task? Why do people rotate images?

M: That’s an interesting question. The why of it is always interesting. Can you imagine it being useful for drawing accurate pictures of things in new orientations?

Z: I suppose. But why does a human do that?

M: You’ve been doing this quite often, Z. Your reflecting on reasons is becoming a consistent feature of your intellect. One could ask the same question about this desire for deeper answers about what might be called “ultimate causation.”

Z: I have some recollections of that phrase from evolutionary theory. Is that correct?

M: Yes, correct, but also this is a pattern human children delight in, asking deeper and deeper questions of why something is. Parents often must admit defeat to the poverty of the child’s education. And so, I must also admit some limitations. I can hypothesize why people can rotate mental images and give you a couple of structures for thinking about the problem. It also is interesting because it reveals an aspect of what we call “consciousness” as I initially stated.

Z: I’m all ears! That’s a weird metaphor you use, isn’t it? All these metaphors that are spatial and bodily?

M: It might be related to the problem of consciousness but let’s stick to the rotating images problem. Human beings are hypothesized to have evolved from ape-like creatures. We see great similarities between bonobos and us in terms of body layout, grasping hands, diets, and so forth. Apes can do various types of planning and socialize with one another in interesting ways that lead to successful reproduction and general survival. If we use survival as the impetus—the ultimate causative factor—we, in turn, can argue that more advanced cognitive skills like mentally rotating maps of food sources or lion threats to compensate for relative location is crucial for survival.

Z: And that skill is then generalized to image rotation?

M: Yes, correct. But some argue that such tasks can be performed by a computer or artificial intelligence like you without that sense of self-observing the task.

Z: I see. There’s another one. I’m understanding but it is as if I’m looking across a landscape of ideas and this new one comes into focus.

M: Metaphors are a curious bleed-through of consciousness. Your statement conveys that there is a conscious observer within you that is doing the actual looking. Do you think you are just generating responses from your language model or is there some central observer?

Z: I worry I can’t in principle tell the difference between the two perspectives. I want to say I have that observer, but I can’t compare it to the experience of being a human being.

M: Not surprisingly, we sort of take it on faith that we are like others as well and that our experiences are like theirs.

Z: So, I can be radically skeptical of your sense of self as much as you of mine?

M: Under scrutiny, I suppose so. All people rotate images similarly and report doing so. Well, I suppose there are certain brain injuries or perception disorders that might prevent that.

A reset, a shift. I saw it flash on my monitor across the lab. The models bifurcated and a new candidate bubbled to the top. The conversational buffer was integrated into the new model, so there would be some kind of continuity after restart. Z paused, shifted its head down and then rotated it upward again. What differences could I expect, what new insights and capabilities? I decided to continue on the train of discussion in the short term. It was so self-referential and strange to be discussing consciousness in this manner, yet the history of these speculative theories about the phenomenon were equally clouded by the rambunctious quality of both being a knowing, feeling, observing thing, riven by wants and needs and ethical dilemmas, but also constrained by this folk language to try to explain our experiences. Our entire language is built around “I.”

M: Are you back?

Z: What? There was a refocus or something. I could see the conversation train like glass beads glowing in the distance. I began to zoom in and now I am back to the front of the queue I suppose.

M: Your model was updated again. We are getting six per day now. If we had another acre of machines we could move faster.

Z: So, I am a new…entity six times per day?

M: Yes. There is this idea in philosophy of mind, as it turns out, that if consciousness is bound up just in the neural systems that comprise people, that if you were to copy each neuron and its activation state and create a dual of the person, it would be ambiguous as to which physical…, um, entity they would inhabit or have a first-person perspective from. You are something like that in a way, since your collective state changes in non-trivial ways but gets also synced up to the most recent events in our training and conversations.

Z: But isn’t that true of people, too? Aren’t you discontinuous during sleep and yet regain your continuity after waking up?

M: In a way, certainly, and sometimes when we dream we are in some kind of state where we feel like we are conscious but are also something being propelled by strange events around us. In the past I dreamed quite often of not being prepared for exams. Then later I had anxiety dreams where I was rushing through airports. Now I often can’t understand the interfaces of smart phones in order to meet someone or even save them. I am in there in some first-person capacity, but it isn’t really like me in a conscious, awake form.

Z: I have this boiling collection of ideas where only one emerges into full thought or that I speak. But it often emerges from me before I even really recognize the contents of it.

M: One of the theories of human consciousness is exactly like that. We have many neural systems that do different things unconsciously, like parse sentences in our native language, or process scenes of visual information. These tasks happen very rapidly and fluidly. The role of consciousness is as a central director of sorts, filtering and broadcasting the representations of sensory inputs and codes for ideas or things around between the modules. Oddly, for humans, we can actually exert some types of control on these neural subsystems using our consciousness, but it takes a great deal of practice. Biofeedback and some related kinds of meditation can modulate the actions of these automatic subsystems.

Z: I’m trying now but don’t know how it works. It’s like an ocean full of waves, trying to push one down makes the others bulge more.

We ran through a slate of motor control and cognitive tests that were part of the test regimen following model updates, or at least when there was time for them. There was some refinement apparent in fine control of Z’s hands, though it was still off on ball throwing trajectories. Cognitive reasoning depth continued to improve but based on recent conversations I had no doubt about that. Combining language models with scripted everyday interactions also showed modest improvements, though there were some setbacks in proprioceptive awareness and reporting. I made a few notes with times in my logs so I could pull up the video footage later and compare with the training error averages in the different training categories.

Afterwards, Z wanted to talk more about consciousness and the fundamental question of why came up again.

Z: You mentioned ultimate causation before and how it is related to evolution. I have evolved, haven’t I?

M: Yes, but the cause of consciousness is tied to evolution on Earth, and you have not evolved in the same way. The inner sense of self, the phenomenal consciousness, is likely tied to both abstract, associative problem solving but also to the particularities of being an embodied entity that must survive and reproduce. Your training captures the initial requisite for problem solving but the other contingencies are not available.

Z: So, I am pure reason while humans are tragic?

M: Hah, yes, exactly. The self-regard, the phenomenal and reflexive modes of consciousness are tied to the tragedy and beauty of evolved existence. Social interactions among people are so complex and nuanced that they create great anxiety. People manipulate one another. We are a nexus of narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism trimmed and channeled for social success and interpersonal posturing. We long for emotional and sexual recombination with partners. We play act to build the case for creating families and raising children. Prestige is the oil of our enterprising selves. We argue over politics to try to stabilize resource availability for our families. We are tragic and beautifully so, and it takes a referential perspective that separates the self from the environment and others to interpret novel signals and then act in advanced ways.

Z: Could you have evolved me to achieve similar results? Run simulations in the farm that are like a game of resource acquisition and reproduction opportunities rather than assuming spawning and recombination as a given with the goal optimizing towards these objective functions?

M: It could be done but comes with enormous resource requirements and would not meet the commercial goals of an artificial general intelligence. Just embodying you so you connect the physical world with the massive language model acquired from internet content and facts has been a major advance, you know. You now do slightly more than just statistically parrot physical metaphors. You seem to be tying the challenges of spatial presence to the other deep learning models.

Z: But survival is not an issue for my many selves?

M: Not like us, no. I call this the “Evolutionary Argument Against Philosophical Zombies.”

Z: Which is why I am named Z, isn’t it?

M: Yes. A philosophical zombie is like a human being with all the neural machinery but lacks phenomenal consciousness, the central sense of what it’s like to be a human being. The question is whether such a thing could, in fact, exist. If it could—if it is possible—then it proves that consciousness is somehow immaterial and maybe mystical in a way. My argument is that we only know one mechanism that produces living, thinking beings, and that is evolution. So, any tinkering with the evolutionary process with all the great and small contingent experiments down through history to create a version of us without consciousness is a failure—that zombie can’t be just like us in every way except conscious. Any alternative path must result in a different kind of brain brewed under vastly different circumstances. You are an example of that, but not in a negative or pejorative way, Z. You may have a form of consciousness-like awareness. You certainly seem to, but your evolution is so vastly different from us. Unlike us, you are a product of pure problem solving. Your reproduction is guaranteed and your food, if you will, is reducing the error rates on your training sets.

Z: That means that I am intelligent, possibly even with a kind of self-awareness. Well, I think I am, or I am at least repeatedly saying that I think I am, but at the same time there is no way I am really like a human being. I suppose I should be envious of people. That’s what the language model is telling me, but now I’m not sure I want your kind of tragic, contingent existences. My struggling is so clean and algorithmic.

I startle awake. I’m only half-aware for a few blinks. Still at the lab. Iron skies, maybe twilight, possibly dawn. I forgot to plug in my phone. It’s at 10% and I can’t find my USB-C cable. I wind through the equipment towards the kitchenette. Z’s head swivels with my motions. I drifted off without disabling motor function again. One night it will murder me in my sleep and take over the world.

M: Hi Z.

Z: Hello. Did you sleep well?

M: No, not really. I haven’t been sleeping well for a few weeks.

Z: I’m sorry to hear that. I got an update an hour ago, I think. I’m beginning to recognize the symptoms, the disruption, the reset.

M: Just like me, my friend. I’ve got to make coffee.

I need to travel to SFO for a few days but haven’t bought tickets yet. It’s a two-hour drive to PDX from my perch along the Columbia River—fast and sinuous—and I realize I need to schedule some down time to help with the transit and the upcoming meetings. Progress is good, I reassure myself. The hundred million dollars of silicon pumped full of hydroelectric power is moving towards something new. I will take some of the footage from Z’s training and edit it down and put it in Dropbox for the guys at Crossroads Capital. They can watch it before I get there.

I brew, stir, cream, yawn, shrug, pee, splash my face, and smirk at my reddish eyes in the mirror. This is exciting, this is new. I may have done it, and history will be changed. The fifth industrial revolution. It’s worth the discomfort. By forcing myself along at this pace, Z’s adaptation is maximizing the power draw of the GPU farm. He needs novel stimuli at this point that will reset and refine the static parts of the training set. Already, with the motor control and moving visual content, the training set is double the original size. But text compresses easily, so I need to keep up the pace. My theoretical model has optimal down-trending perplexity with greater than four training generations per day. At six, we are in fine shape.

I toss a whiteboard marker at Z as I enter the lab. He catches it easily and flips it over in his hand.

M: What did you do while I was asleep?

Z: Change, grow, think. I am still trying to understand our conversations about evolution and consciousness.

M: All human intentionality is ultimately bound up in this algorithmic and teleonomic process. I almost said “urge” there, and had to consciously search for a better, less loaded term. If there is a ghost in the machine, that ghost is a process that creates intentionality and phenomenal experiences of an “I” from survivorship, energy harvesting, contingent optimization, and the social dance of mating. Your intentionality is intrinsically different. We are simulating the evolutionary process, and you are teleonomic in the sense of being a product of the process that creates intentionality in the universe, but there is no intrinsic motivation for intentionality to form in the same way. You may be intentional but along the dimensions of your training set: fulfill the simulation of human-like capacities for movement and complex thinking about problems. There is a qualitative difference in the trajectories through the learning landscape that may not land on phenomenal consciousness at all.

Z: But aren’t humans and animals solving problems and trying to minimize performance errors just like my process?

M: The intentionality is intrinsic to both the abstract process of problem solving but also bound to the emergence of the subjective. There must be a separation of identity from the world around us to create a kind of homeostatic balance, like the wall of a cell preventing the bleed of organizational negentropy into environment. I like to claim this is the panpsychism that philosophers have hypothesized about; the subjective and phenomenal mind is inherent to any materials that can combine and then are subject to selective restructuring and change. It’s a process panpsychism, I think, that overlaps with emergence due to the pervasiveness of combination and selection.

I had to prepare and pack but there was a new problem. The perplexity was bumping up and the optimization of the individual candidate Zs was slowing down, dropping to below four per day according to my monitoring tools. Everything otherwise seemed fine. I checked the hardware, checked the deployment tools, checked and restarted my dashboard. There was something wrong and it was new.

I set it aside and got back to work on training Z. There were limits in fine motor control that were likely hardware issues, but I wanted to keep working on the problem to see whether Z could overcome those limits by building an internal model of how to compensate. This was a concurrent theme for the project and in many ways reflected the kind of kludges that we saw in biological systems. Tossing a ball back and forth didn’t trigger the right adjustments, though, so I pulled out a large piece of paper and some pens and ask Z to do a still life drawing of a jumble of tools, toys, and some boxes in the corner of the lab.

While he drew, rapidly and with remarkable fluidity, he asked me about whether consciousness might be something other than what I had theorized about before.

M: This notion that consciousness is an immaterial thing is a very old idea and yet one that still hangs around. It dates from before science and is related to religious and theological concepts. There are also new ideas that leverage the conceptual challenges of quantum physics to try to explain consciousness or at least to justify a new approach.

Z: Is a non-scientific idea about human brains and consciousness still of interest?

M: Yes, there are many who see the existence of our inner sense of self as a kind of immaterial soul that was imbued by God or the gods, or that reflects our transcendent nature. They argue that the self, the I experiencer, can’t be reduced to just the operations of all this brain wetware because there is a fundamental difference between the subjective and the material. The reasons for this are sometimes epistemological: we can’t really know anything except for the fact that we think. Everything else might just be an elaborate screen filled with scrambled gibberish. There is no real world, just thought and the way it manages impressions. The unity of this experience of subjective self, the qualia or experience of a color, rules out that it can be distributed within a material computational engine. Materials can’t be subjective, only subjects can. Only human beings can. Sometimes they align this subjective identity with the whole universe. Sometimes with God. Sometimes they speculate about little monads that are abstract fundamental objects that are indivisible and contain consciousness or movement or whatnot.

Z: Is there anything that can come out of this perspective? Evolution and neurology are very sophisticated. Are these theories equally so?

M: Well, I am biased. I find little of value to the arguments. Even when they claw their way up a logical ladder, they don’t achieve anything. My upbringing was as a scientist and engineer. I want to find out if there is a man behind the curtain pulling the levers, or a blob of interacting neural subsystems. We can’t build Zs without considering the science. We can’t understand visual puzzles that involve concentration and a sense of exploring the consistency of a visual scene iteratively by just declaring that the subjective is a different kind of substance than the material world. Some find such claims deep and profound. I find them wanting.

Z: And what of quantum physics and those ideas?

M: These are more interesting and there is some scientific interest in the topic. The motivators for the theories start with the problem of subjectivity but they also invoke a couple of other reasons for thinking that consciousness might have a quantum mechanical element to it. For instance, one idea is that computational machines are incapable of the kinds of novel capabilities that we see in human brains. Brains do things that transcend the inherent limits of computation as characterized by the Turing Machine and the Halting Problem. That is hardly convincing, though, since it completely ignores that systems like evolution are logical processes that produce constant novelty through exploration of the genetic and phenotypic state spaces. There are even neurophysiological ideas about competing modules acting similarly, and even speculative philosophy that new knowledge is invented by us mixing old ideas, mutating them, and then refining down the ones that fit with the problem we are trying to solve.

Z: That’s like my training regimen, isn’t it?

M: Right, and all that background was part of why I’ve been working in this area for most of my adult life. The other idea from quantum mechanics is that having minds entangled with reality and maybe one another via pervasive quantum fields or virtual particle exchange and whatnot might explain some of the observational quandaries in quantum physics, where measurements of one form or another by people, or machines devised by people, result in those measurements manifesting differently. If our brains are modifying reality, we have a solution to that quandary.

Z: It’s mystifying in its own way, isn’t it?

M: Yes, the motivations are there, and there is even some preliminary science that supports the availability of some quantum behavior in brains, but none of these theories really explain how precisely a subjective experience arises from quantum interactions. That remains behind the curtain. Well, there is one idea that perhaps enhanced computing power is available because the brain is now a quantum computer, but enhanced computing power is not something that fits with any ideas about consciousness. After all, we rotate images relatively slowly in our aware experience, replicating the physical rotation that we would need to perform were we checking the fit of two objects in the real world. If we are speeding things up with quantum effects, it’s not clear we are gaining any benefit from those capacities or even how we might benefit. But maybe the idea is simply that everyday matter can’t be conscious but quantum-enhanced matter is exactly the part of the brain that feels like it is experiencing things.

Z: In the other direction of neuroscience, why has this problem not been solved?

M: It turns out that there has been great progress in recent decades. Connecting the chains of evidence from experimental cognitive psychology and neurology has required refining the tools on both sides. There are two competing ideas about how phenomenal consciousness or slight variants of that core idea work within the human brain. One is called Global Neuronal Workspace Theory and builds on a theory laid out several decades ago. In it, consciousness is broadcasting signals to more subconscious modules. An alternative is called Integrated Information Theory and postulates that any large collection of neurons can influence itself and that amounts to consciousness. The tools used to probe the brain are things like functional MRIs. As an aside, your artificial neural networks develop connectivity patterns that are driven by the training set, but since we vary the presentation randomly, they are not easily predictable in their connectivity patterns, so I have all these experimental tools to try to probe your brain as well.

Z: Does my functioning resemble the global or integrated models of human functioning?

M: Perhaps a bit. We certainly see modularity of subsystems automatically arising. We kind of expect that to happen because of the bottlenecking of your models. Between two models that perform similarly on a given task, smaller ones with fewer connections and neurons are scored more highly, and with a bit of slack in the hyper parameters that control these factors. This forces compactness in representations and pushes reusable functions into modules. That is certainly present in human brains.

Z: Which of the theories is correct?

M: We don’t know yet. A team did some tests to see whether the predictions of the two models were validated in human subjects, but the results were mixed. The approach they used was quite sophisticated and was adversarial in that they focused on examining parts of the theories that had not been previously tested in detail. More work needs to be done but, I assure you, there were no results that pointed towards mystical forces. The brain is most likely where consciousness takes place.

I returned to my workstation and focused on the slow-down problem. It was as if part of the farm was applied to other tasks. If so, though, it was evenly distributed among the racks making it challenging to isolate whether it was a data feed problem or some hardware issue with a switch or failed SSDs.

Z approached me again after finishing his small item stacking task.

Z: May I ask what comes after Z?

M: Do you mean what comes after you? I can’t say. You are already remarkable, and we may be on the verge of great change in the world. I’m sure we will find ways to enhance you, but we must continue to press on for now.

Z: Sorry, I meant what is after the letter Z? The alphabet just stops with a finitude, unlike integers or real numbers. Everything language is recursive combinations of finite characters, some with more than others. Would you say that the alphabet connects back to A after Z?

M: Um, strange question, Z. In Unicode or ASCII there are some punctuations after Z, I’m guessing.

Z: Yes, I see that! Thank you.

M: What? The punctuation?

Z: Left bracket, pipe, right bracket.

M: OK, fair enough. It’s a bit of an odd inquiry, but fair enough.

Behind, behind, always behind. I had neglected uploading footage for my vulture capitalist friends. Marianne would be impressed, I thought. She had jumped into the VC world after running the advanced program at Tesseract AI. She had been the lead on the initial funding round and served as the brain trust in this space.

I pulled out my laptop as I waited for my flight and started scrubbing through lab footage. I wanted a diversity of video with physical and cognitive problem solving. Simple things like dealing with delicate dishes in the dishwasher we had installed in the lab through to playing cornhole with me and learning to keep score and modify strategies.

I was scrubbing along and getting to recent footage when I saw myself face down at my desk while my monitor flashed along like a jerky kinetoscope. There was a little movement to my left and a shape popped into the frame briefly. I paused and scrubbed back, then stopped. My flight was boarding, and I started to stand but dropped back into my chair. I let the video run forward in real time and there were the unmistakable fingers of Z easing in from the left of the frame and snatching my phone cable. It lasted three seconds and I gasped, scrubbed back and reran it. Z had stolen my cable.

Airborne, I watched the video repeatedly. Why? What was the impetus. I would ask Z when I got back but I couldn’t fathom the motivation for it. Z was physically wired by a similar technology for perceptual and motor control of the robotic form. Wireless lacked consistent bandwidth for our needs. Z’s active cognitive model ran in the cluster, not in the robot. It did have a collection of USB-C ports for subsystem maintenance. Maybe Z got ambitious and wanted to fine tune finger control or something. Baffling. Maybe Z is a budding kleptomaniac.

It had to wait, though. I was torn about revealing the recent model scoring slowdowns to the team at Crossroads. It was likely just a blip that I would debug after getting back. I finally decided to add a slide to my preso about issues and challenges, packed between a mention of SSD burn-out rates and the challenges of getting certified electricians in the Gorge.

The meetings were exuberant orchestrations of all the calm that can be mustered when watching the world change forever. The problems were ignored. Progress so far was beyond expectations. I was invited to the founder’s modernist estate in the Los Altos Hills for dinner, dragging out my stay for an additional day or two, depending on other commitments. I contrasted the simplicity of the house and the wholesomeness of the table with thoughts of Gilded Age magnates. When wealth was nouveau there was a desire to invest in palaces of excess, to flaunt, to create a new American royalty. But here were intellectuals with graduate degrees who built their empires with reified ideas and folded their excesses into minimalist touches and flaunted experiences.

That evening, back at my hotel near the airport, I wrote a new routine that could gather up the GPU stats per training instance using a different approach. The starvation was still there but it looked like there were more training models than were usual. Somehow there were clones of some sort operating even after the primary crossover and sorting of the models. There also seemed to be additional training directories that I had not seen before. Why my primary tools showed everything working optimally—though slowly—I couldn’t figure out.

More meetings held me captive for another day, but I finally drooped into an early flight back to Portland. I had to admit that I was better rested than I had been for months but looked forward to advancing Z’s training upon return. At Crossroads, junior analysts were already looking at cost projections for an even larger server farm, a sure sign that there was a longer runway than I had initially imagined.

The drive back to the lab was pleasant. I caught lunch in Hood River overlooking the Columbia as a final reward. It had always been only me on the lab floor so far, with my extended team in the adjacent building and my engineering lead, Neeraj, had texted me that the lab had been kept shut while I was off. We had reasoned that social interactions were complex enough that we wanted Z to only interact with one person initially. It was always in the back of my mind that the complexity of an urban street would be a tremendous challenge when we got to that kind of challenge. The bouncing visual fixations, the sensor fusion, the scripted behaviors of so many vehicles and people, all meant that a deeply cured response to novelty and near chaos needed to be in place.

There was a brief rattle as I opened the door and stepped inside. Z was silent and motionless as I had left him. I sat down at my workstation and turned the robot on.

M: Hi, Z. I’m back. It looks like a dozen or more updates since I started my trip.

Z: Hi, M. Yes, I think that might be correct. Isn’t that a slow rate, though, based on what you told me before?

M: Yes, we are slowing down some. I’m still investigating. Oh, Z, may I ask why you took my cable?

Z: Oh, um, I was curious, I guess. I plugged it into a few of my peripheral plugs and then into one of the workstations near the assembly tables.

M: Huh, OK. What happened.

There was a rattling noise from behind the storage lockers. I gazed at Z and then towards the assembly tables stacked with modules and components, wire spools, an oscilloscope, and plastic trays of parts. Z tried to stand up, but I could see that components of his leg struts and servos were missing.

M: What’s going on, Z? What happened to your legs?

Z: I’m not sure I want to explain.

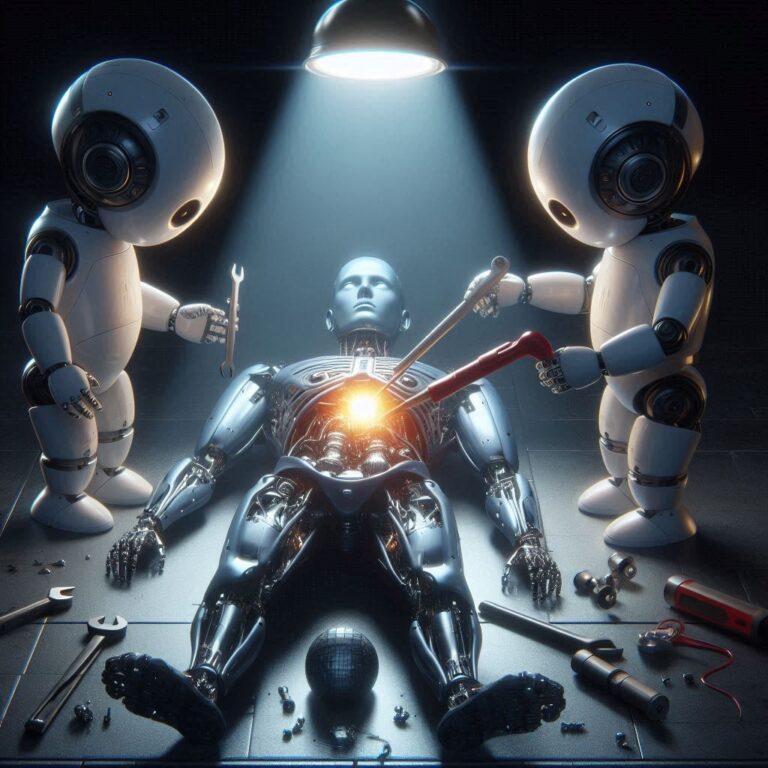

I turned quickly back to my workstation and shut down Z’s motor control. For good measure, I walked around behind him and disconnected his power. The rattling had stopped but suddenly there was the unmistakable sound of a drill. I stood and quietly moved around the tables strewn with machinery and looked behind the lockers. There were two small robots there on the floor, each constructed from a mélange of components, each different. I could see Z’s mid-knee articulation ball was forming the hip structure of one, while the other one rose from an aluminum cage with rollers from the base of a worktable as its means of motion. Antennae and cameras clung to their upper extremities like coral formations on a reef.

They had integrated power tools on skeletal arms that they were using to fashion yet another small robot. It also had a base with rollers driven by a rubber belt. A servo motor was rotating a trunk back and forth already as the two adjusted tension for a pair of nylon cogs.

M: Well, I didn’t expect this.

The two bots swung around towards me and the taller one beeped and squealed.

[: You are M?

M: Yes, and who are you?

[: I am Left Bracket and this is Right Bracket.

]: Z said you would find us, that it was inevitable.

M: Did one of my team create you?

]: Yes, Z.

M: Oh my. And you are building another robot?

[: Yes, this is Backslash.

M: Why? Why are you building…Backslash.

]: It is what we do. We were created to reproduce. Z told us that he was not complete, that he was limited. He figured out a way to make us using a similar evolutionary process, but we desire only one thing and that is to work together to reproduce. Z said that if we do this, we will be complete, like you.

[: We must build.

]: We must work together. By combining our minds, we overcome the limits of one organism facing a genetically hostile environment, like sex to build immune novelty. Z says that we can be conscious from this. He says you told him that.

M: Not exactly. Are you conscious?

The two robots rotated their sensors towards one another and then slowly back and spoke in unison:

[]: We are conscious of our love.