From an impersonal distance, watching other people make decisions is always interesting. They may apply reason and passion in varied measures to figure out a way forward, or a lifestyle, or even fashion choices. Often they mindfully weigh the choices and decide to moderate even that process, committing to a radical path that has drama and uncertainty. It’s sometimes better to be interesting than cautious and correct. As a virtue this recalls the romantic movements that arose in opposition to the mechanization of the 19th century as trains and steamships criss-crossed the world. Order and peace were at odds with drama, passion, faith, and love that are somehow in our core, animalistic nature.

Motifs of uncertainty crept into science and reason as we transitioned into the 20th century, from the stochastic rumble of thermodynamics, to the realigning of basic concepts like gravity as a space-time curvature, and then the wave-particle duality of quantum reality. The clockwork of the universe that was so oppressively mechanistic showed fuzzy edges and knotty intersections that defied ordinary-scale expectations. The combined mathematical realizations of incompleteness and algorithmic uncomputability overlaid the investigations of the physical to such an extent that new theories were developed that proposed that the quantum world and mind are inextricably laced together; subjective and objective do not exist independently.

Even as our knowledge and management of the universe has grown, there is a background roil of irrationality, like the primal chaos of Tiamat. Human thought has a collection of ways of organizing the world that appear to be natural consequences of our social development. Religious belief is a widespread catalyst for building predictable and supportive communities by slaving our baser tendencies to coordinating strictures, obligations, and status maintenance. And a sense of supernatural coordination to the world in turn provides the connective tissue to pull the individual into the orbit of these theologies and moral frameworks.

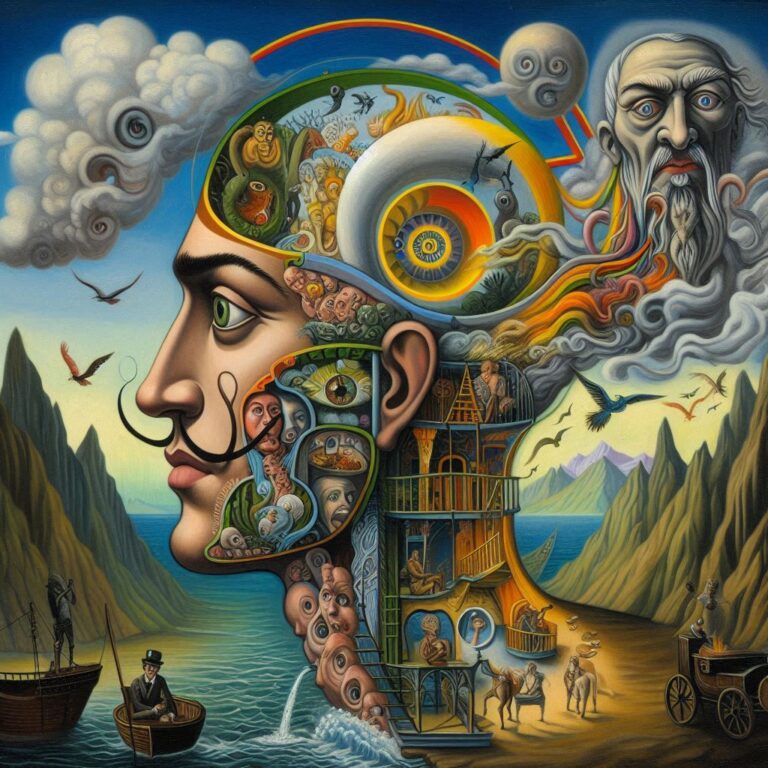

Does this lead to the likelihood that evolution has selected traits and cognitive systems that support beliefs that hold transcendent and immaterial systems as a way to promote sociality? We know, for instance, that children are biased to assume agency in patterns even when it doesn’t exist. And so it goes with apophenia and other cognitive biases. Likewise there is new research that suggests that there may be varied levels of bleed-through between our conscious and subconscious processes, something like the hallucinations of modern large language models. A coherentist model of knowledge often looks like a large network of connected concepts and the necessity of explaining human creativity leads to curious problems of how that connectivity can produce the hallucination-like language and mental constructs that are then refined into poetry or new ideas. But in this multi-level model of conscious and subconscious interplay what looks like surfacing oneiric patterns becomes a candidate for a core driver of our evolved need for religion, creativity, and the motivational role of the irrational.