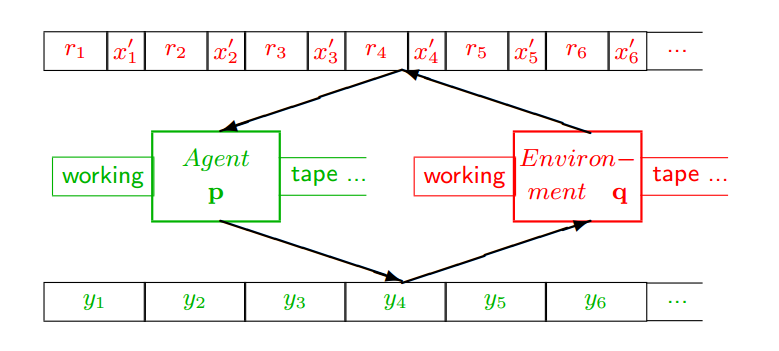

Continuing to develop the idea that social reasoning adds to Hutter’s Universal Artificial Intelligence model, below is his basic layout for agents and environments:

A few definitions: The Agent (p) is a Turing machine that consists of a working tape and an algorithm that can move the tape left or right, read a symbol from the tape, write a symbol to the tape, and transition through a finite number of internal states as held in a table. That is all that is needed to be a Turing machine and Turing machines can compute like our every day notion of a computer. Formally, there are bounds to what they can compute (for instance, whether any given program consisting of the symbols on the tape will stop at some point or will run forever without stopping (this is the so-called “halting problem“). But it suffices to think of the Turing machine as a general-purpose logical machine in that all of its outputs are determined by a sequence of state changes that follow from the sequence of inputs and transformations expressed in the state table. There is no magic here.

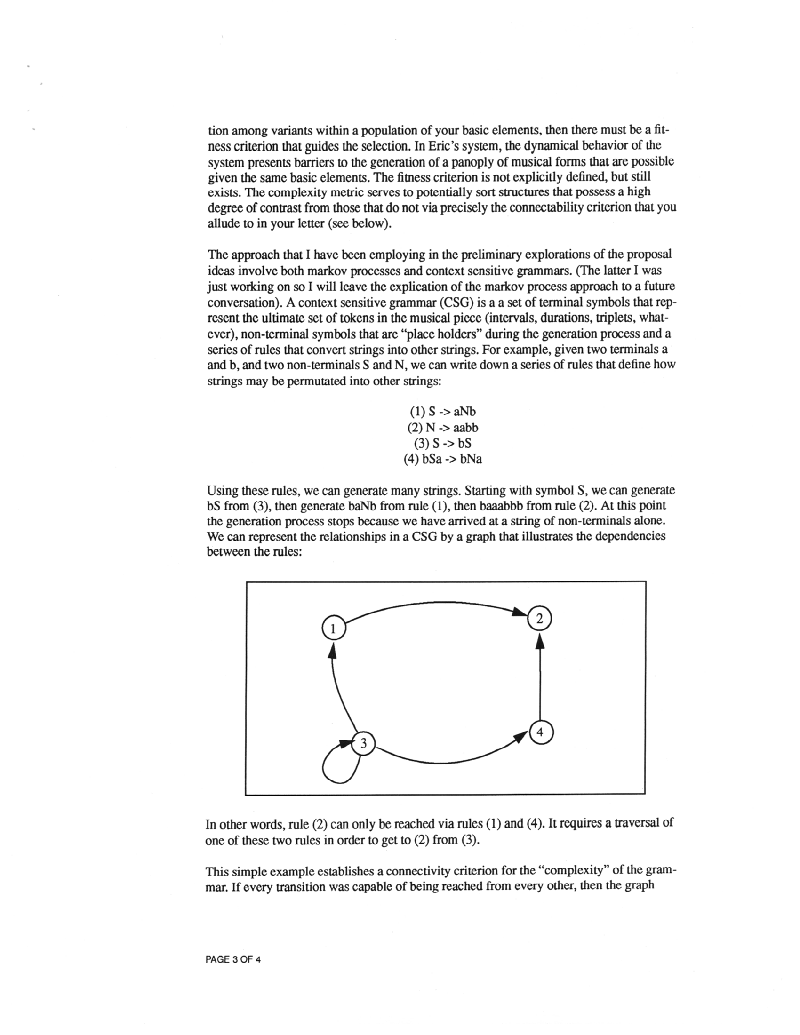

Hutter then couples the agent to a representation of the environment, also expressed by a Turing machine (after all, the environment is likely deterministic), and has the output symbols of the agent consumed by the environment (y) which, in turn, outputs the results of the agent’s interaction with it as a series of rewards (r) and environment signals (x), that are consumed by agent once again.

Where this gets interesting is that the agent is trying to maximize the reward signal which implies that the combined predictive model must convert all the history accumulated at one point in time into an optimal predictor.… Read the rest

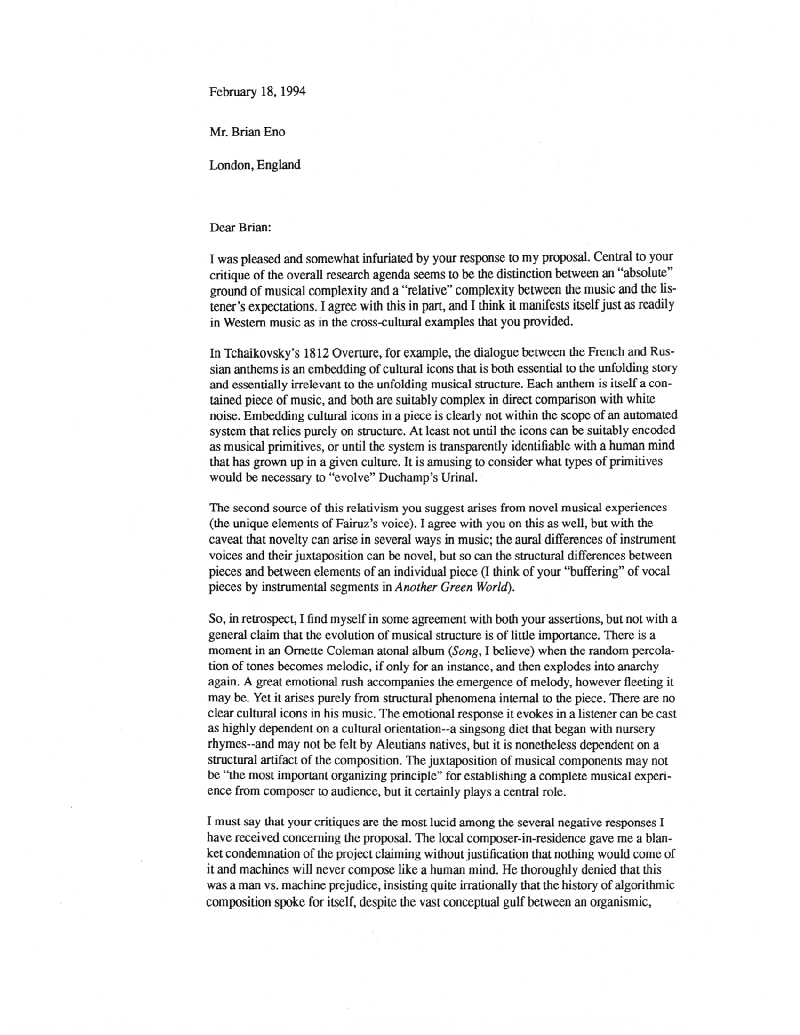

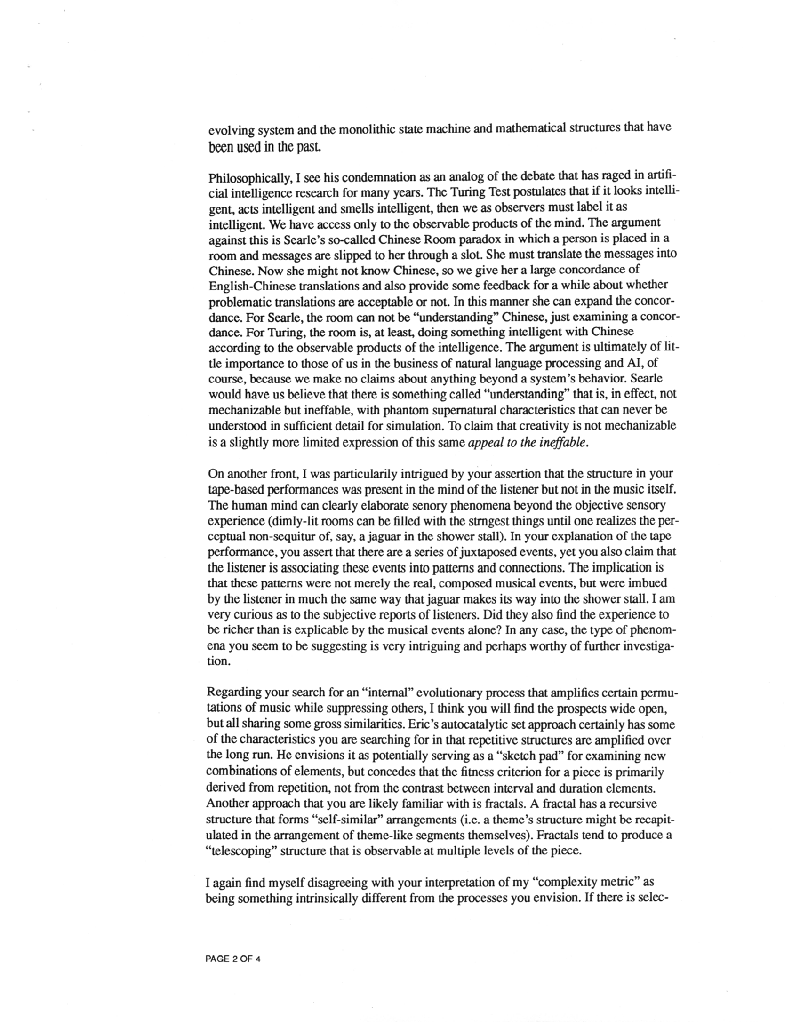

The impossibility of the Chinese Room has implications across the board for understanding what meaning means. Mark Walker’s paper “

The impossibility of the Chinese Room has implications across the board for understanding what meaning means. Mark Walker’s paper “