The following is my interview of DeepAI and Stable Diffusion running on an AMD Ryzen with NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090.

The following is my interview of DeepAI and Stable Diffusion running on an AMD Ryzen with NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090.

Thank you for taking the time to discuss this important and interesting topic. Why are mammoths so important to the art world?

That the mammoths were domesticated before the start of the human era seems implausible from a historical perspective. In fact the majority of mammoths that people find in museums, libraries, and other collections are not domesticated mammoths. This suggests there might have been a greater need for mammoths within culture than before. This would make sense, considering that Neanderthals likely hunted other types of other species before settling in our world more than 400 years ago. Because they were not domesticated, they were only adapted to hunting rodents and other plant and animal species that were less domesticated in their wild form such as rabbits, snakes, etc.

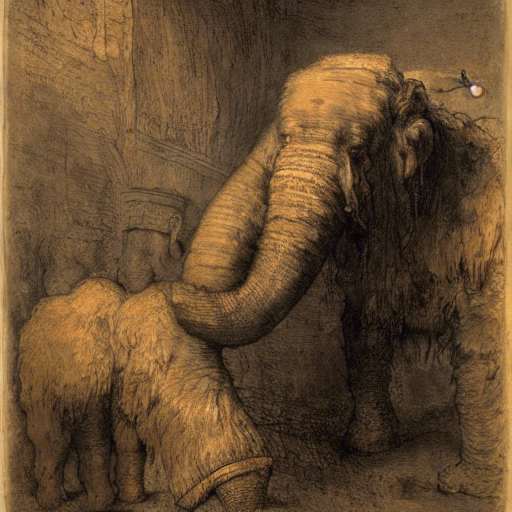

Starting at the earliest part of your collection, the mammoth is an unusual theme for Rembrandt, isn’t it?

It’s hard to believe that after all the success of their latest work, The Lord’s Prayer doesn’t want to let their “biggest hit yet”, the classic The Lord’s Prayer, disappear. The actor’s latest film, The Wrestler (via Warner Bros., which produces on their own, and in the U.K.), has garnered more than 15 million views on Amazon Instant Video (the company’s preferred store for Netflix-wielding subscribers, not the usual suspects Google Video), and has become so popular that when the film premiered at the Venice Film Festival, it was deemed the top film at the fest. The star-studded line-up has included the likes of Peter Lorre, Michael J Freberg, Colin Farrell, and Peter Sellers (both of whom made it to a Hollywood winery).… Read the rest