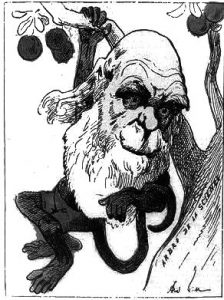

The is-ought barrier is a regularly visited topic since its initial formulation by Hume. It certainly seems unassailable in that a syllogism designed to claim that what ought to be done is predicated on what is (observable and natural) must always fail. The reason for this is that the ought framework (call it ethics) can be formulated in any particular way to ascribe the good and the bad. A serial killer might believe that killing certain people eliminates demons from the world and is therefore good, regardless of a general prohibition that killing others is bad. In this case, we might argue that the killer is simply mistaken in her beliefs and that a lack of accurate information is guiding her. But even the claim that there is an “is” in this case (killing people results in a worse society/people are entitled to be free from murder/etc.) doesn’t really stay on the factual side of the barrier. The is evaporates into an ought at the very outset.

The is-ought barrier is a regularly visited topic since its initial formulation by Hume. It certainly seems unassailable in that a syllogism designed to claim that what ought to be done is predicated on what is (observable and natural) must always fail. The reason for this is that the ought framework (call it ethics) can be formulated in any particular way to ascribe the good and the bad. A serial killer might believe that killing certain people eliminates demons from the world and is therefore good, regardless of a general prohibition that killing others is bad. In this case, we might argue that the killer is simply mistaken in her beliefs and that a lack of accurate information is guiding her. But even the claim that there is an “is” in this case (killing people results in a worse society/people are entitled to be free from murder/etc.) doesn’t really stay on the factual side of the barrier. The is evaporates into an ought at the very outset.

There are efforts to enliven some type of naturalistic underpinnings of moral reasoning, like Sam Harris’s The Moral Landscape that postulates an adaptive topology where the consequences of individual and group actions result in improvements or harm to humanity as a whole. The end result is a kind of abstract consequentialism beneath local observables that is enervated by some brain science. Here’s an example: (1) Better knowledge of the biological origins of disease can result in behavior that reduces disease harm; (2) It is therefore moral to improve education about biology; (3) Disease harm is reduced resulting in reduced suffering. This doesn’t quite make it across the barrier, though, because it presupposes an ought for humans that reduces the imperatives of the disease itself (what about its thriving?),… Read the rest