E.O. Wilson charges across the is-ought barrier with a zeal undiminished by his advancing years and promotes genetic diversity as a moral good in The Social Conquest of Earth:

E.O. Wilson charges across the is-ought barrier with a zeal undiminished by his advancing years and promotes genetic diversity as a moral good in The Social Conquest of Earth:

Perhaps it is time…to adopt a new ethic of racial and hereditary variation, one that places value on the whole of diversity rather than on the differences composing the diversity. It would give proper measure to our species’ genetic variation as an asset, prized for the adaptability it provides all of us during an increasingly uncertain future. Humanity is strengthened by a broad portfolio of genes that can generate new talents, additional resistance to diseases, and perhaps even new ways of seeing reality. For scientific as well as moral reasons, we should learn to promote human biological diversity for its own sake instead of using it to justify prejudice and conflict.

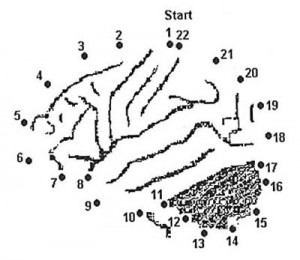

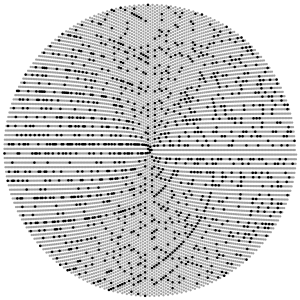

This follows an analysis of the relative genetic differences between various racial groups of humans, concluding that subsaharan Africa contains the highest genetic diversity among human groups. Yet almost everything in our social and biological history suggests that we have formed social structures specifically to prevent out-breeding and limit the expansion of our genetic pool. This has always been a thorny subject for selfish genetics: why risk pairing your alleles with unknowns guessed at through proximal sexual clues like body symmetry or the quality of giant peacock tails? The risk of outbreeding is apparently lower than the risk of diverse infectious agents according to a common current theory, but we also see culture as overriding even the strongest outbreeding motivation by imposing mating rules based on familial and tribal power struggles. At the worst, we even see inbreeding depression in populations that consolidate power through close marriages (look at the sex-linked defect lineages in European royal families) or through long religious prohibitions on marrying outside of relatively small populations of the faithful.… Read the rest