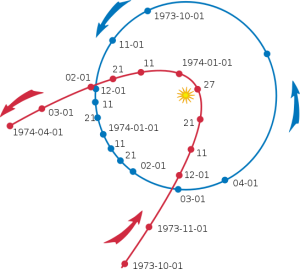

Every few years, with the hyperbolic regularity of Kahoutek’s orbit, I return to B.R. Myers’ 2001 Atlantic essay, A Reader’s Manifesto, where he plays the enfant terrible against the titans of serious literature. With savagery Myers tears out the elliptical heart of Annie Proulx and then beats regular holes in Cormac McCarthy and Don DeLillo in a conscious mockery of the strained repetitiveness of their sentences.

Every few years, with the hyperbolic regularity of Kahoutek’s orbit, I return to B.R. Myers’ 2001 Atlantic essay, A Reader’s Manifesto, where he plays the enfant terrible against the titans of serious literature. With savagery Myers tears out the elliptical heart of Annie Proulx and then beats regular holes in Cormac McCarthy and Don DeLillo in a conscious mockery of the strained repetitiveness of their sentences.

I return to Myers because I currently have four novels in process. I return because I hope to be saved from the delirium of the postmodern novel that wants to be written merely because there is nothing really left to write about, at least not without a self-conscious wink:

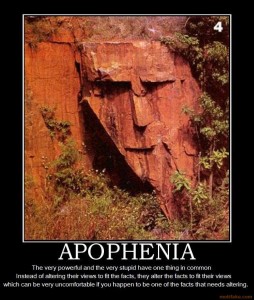

But today’s Serious Writers fail even on their own postmodern terms. They urge us to move beyond our old-fashioned preoccupation with content and plot, to focus on form instead—and then they subject us to the least-expressive form, the least-expressive sentences, in the history of the American novel. Time wasted on these books is time that could be spent reading something fun.

Myers’ essay hints at what he sees as good writing, quoting Nabakov, referencing T.S. Eliot, and analyzing the controlled lyricism of Saul Bellow. Evaporating the boundaries between the various “brows” and accepting that action, plot, and invention are acceptable literary conceits also marks Myers’ approach to literary analysis.

It is largely an atheoretic analysis but there is a hint at something more beneath the surface when Myers describes the disdain of European peasants for the transition away from the inscrutable Latin masses and benedictions and into the language of the common man: “Our parson…is a plain honest man… But…he is no Latiner.” Myers counts the fascination with arabesque prose, with labeling it as great even when it lacks content, as derived from the same fascination that gripped the peasants: majesty is inherent in obscurity.… Read the rest