Thomas Nagel returns to defend his doubt concerning the completeness—if not the efficacy—of materialism in the explanation of mental phenomena in the New York Times. He quickly lays out the possibilities:

Thomas Nagel returns to defend his doubt concerning the completeness—if not the efficacy—of materialism in the explanation of mental phenomena in the New York Times. He quickly lays out the possibilities:

- Consciousness is an easy product of neurophysiological processes

- Consciousness is an illusion

- Consciousness is a fluke side-effect of other processes

- Consciousness is a divine property supervened on the physical world

Nagel arrives at a conclusion that all four are incorrect and that a naturalistic explanation is possible that isn’t “merely” (1), but that is at least (1), yet something more. I previously commented on the argument, here, but the refinement of the specifications requires a more targeted response.

Let’s call Nagel’s new perspective Theory 1+ for simplicity. What form might 1+ take on? For Nagel, the notion seems to be a combination of Chalmers-style qualia combined with a deep appreciation for the contingencies that factor into the personal evolution of individual consciousness. The latter is certainly redundant in that individuality must be absolutely tied to personal experiences and narratives.

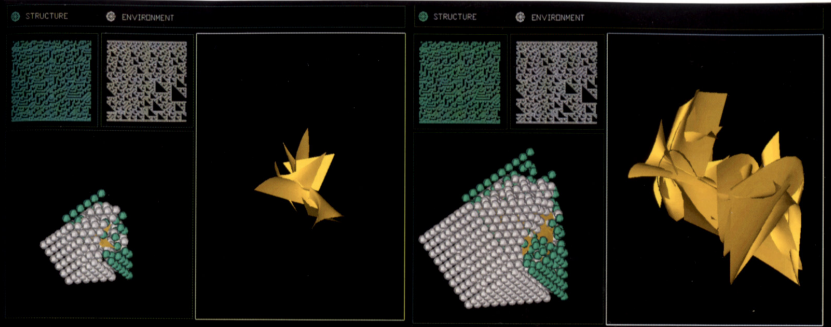

We might be able to get some traction on this concept by looking to biological evolution, though “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” is about as close as we can get to the topic because any kind of evolutionary psychology must be looking for patterns that reinforce the interpretation of basic aspects of cognitive evolution (sex, reproduction, etc.) rather than explore the more numinous aspects of conscious development. So we might instead look for parallel theories that focus on the uniqueness of outcomes, that reify the temporal evolution without reference to controlling biology, and we get to ideas like uncomputability as a backstop. More specifically, we can explore ideas like computational irreducibility to support the development of Nagel’s new theory; insofar as the environment lapses towards weak predictability, a consciousness that self-observes, regulates, and builds many complex models and metamodels is superior to those that do not.… Read the rest