I recently discovered the YouTube videos of Paulogia. He’s a former Christian who likes to take on young Earth creationists, apologists, and some historical issues related to the faith. I’m generally drawn to the latter since the other two categories seem a bit silly to me, but I liked his recent rebuttal of some apologist/philosopher arguments concerning the idea that ethics must be ontologically grounded in something. The argument is of the sort stoned high schoolers engage in—but certainly more carefully attended to—as I commented on the video.

I recently discovered the YouTube videos of Paulogia. He’s a former Christian who likes to take on young Earth creationists, apologists, and some historical issues related to the faith. I’m generally drawn to the latter since the other two categories seem a bit silly to me, but I liked his recent rebuttal of some apologist/philosopher arguments concerning the idea that ethics must be ontologically grounded in something. The argument is of the sort stoned high schoolers engage in—but certainly more carefully attended to—as I commented on the video.

So rather than pick on definitional minutiae, let’s take an expansive view of ethical reasoning and try to apply it to contemporary problems in society. For instance, while all societies have generally condemned murder in one way or another, how do we approach something like whether governmental control or regulation of environmental pollution and interaction is necessary or obligatory?

For the apologist/philosophers in the video, they seem to argue that scriptural claims places a grounding of ethics in a person’s “heart,” but then leave open how that gets translated into some kind of decision-making. At one point, one of the guys says he tends towards virtue ethics, while the other notes that some might see deontological ethics as the proper extension of that ontologically- and theistically-grounded impetus.

Let’s take a minimalist and observational approach to ethical behavior. We can perhaps tease out a few observations and then try to fit an explanatory theory onto that.

- Moral and ethical perspectives are and have been varied across people and time.

- There seems to be some central commonalities about interpersonal and group ideas about what is ethical and moral.

- Those commonalities have reflections in the natural world and among non-human species.

- In recent centuries populations have grown and, largely, misery has declined.

- There have been new tools invented that are used to guide people about how group decision-making helps to reduce misery or, at best, increase general happiness.

- Often, the decision about those tools results in conflict, compromise, or acceptance.

Using a minimalist fitting, then, about all we can conclude is that there is perhaps a bit of grounding of some core ethical concepts in the natural world, but that the newer tools are unique inventions of reason combined with complex social experimentation within and among groups. No surprise there, it’s what we thought in high school and what our textbooks told us, too.

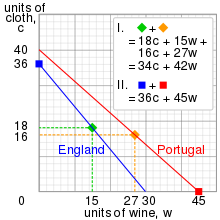

What about the newer tools, however? Where a deontologist or virtue ethicist might have to stretch to determine whether free markets versus regulated ones are more desirable, economics has developed and been shaped and reshaped as an independent social science that strives to answer how regulation and free market principles actually translate into welfare-defining outcomes. It’s not written on one’s heart in any obvious way and, indeed, I would argue that ideas like the Principles of Absolute or Comparative Advantage are neither obvious nor rooted in any kind of ethical framework other than a commitment to reason, and yet they provide a numerical framework by which trade and protectionism can be evaluated to determine what is good.

A recent Bloomberg International article highlights some of ways, for example, that “classical liberalism” (lightweight Libertarianism in American parlance) can be applied to contemporary social problems. The author notes, for instance, that insofar as wealth inequality serves the common good (Rawls), it could be acceptable. Or, alternatively, insofar as wealth was gained by fair means (Nozick), it could also be acceptable. But then we can reason that inheritance taxes can be justified, as well. Similarly, the use of market mechanisms for pollution management (carbon taxes/marketplaces) provides a overlay of regulation for the tragedy of the common waters , lands, and air, that still allows market mechanisms for production to thrive. Similar ideas can assist in the ethics of health care reform.

The non-obvious parts of this, and ideas that transcend any kind of ethical intuitions or philosophical frameworks, revolve around concepts like market failures. If one party has advantageous information (asymmetrical information) that distorts market pricing, for instance, then the good or service might be considered unethically priced. This isn’t simply a matter of supply or demand, but one of extortion or unfairness. Monopolistic behavior is another example.

So let’s get back to ontology and grounding. These economic ideas and our attachment of claims of fairness to them are a result of invention combined with some knowledge of history and a desire to increase the thriving of ourselves and others. The latter may be a consequence of the biological imperatives of social animals that coexist, but doesn’t even have to be; we can also just derive them from reason and a bit of numeracy. As Lord Kelvin said:

When you can measure what you are speaking about and express it in numbers you know something about it.

Otherwise your knowledge is of a “meagre and unsatisfactory kind.” And hence, we get perhaps a bit beyond high school arguments and into the thicket of at least undergraduate topics, but we really don’t need some abstract ontological grounding in more than just reason. Ethics are things we decide on together, through exercises of thought and sometimes a bit of passion, and a result of education.

And here we have this conflict playing out in realtime: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/01/23/mnuchin-said-thunberg-needed-study-economics-before-offering-climate-proposals-so-we-talked-an-economist/