Growing up in New Mexico I had an unusual collection of childhood experiences. My father was a professor of engineering at New Mexico State but had done post-docs in astrophysics at the Naval Observatory in Washington D.C. after a doctorate at University of Wisconsin at Madison. I rode along to cosmic ray observatories high in the mountains and joined him at Los Alamos National Laboratory during summer consulting gigs. He introduced an exotic young fellow professor and his wife to me after I became fascinated by insect vision and ideas for simulating how bugs see the world. That, in turn, led to me living with the couple (he with a doctorate in EE and graduate students in evolutionary biology; her with a doctorate in plant physiology doing cancer research) after my father died young. I slept under a workbench while they started a business and built early word processor systems, pivoted to commercial time sharing, then to consulting on weather monitoring systems for White Sands Missile Range.

I was always in special programs and doing science fairs, taking art classes at the university, and whatnot until it became uncool for me for some reason. In a perhaps not unexpected series of intersections by high school I had a collection of friends who were bright and precocious in their interests in a way that I thought perfectly normal at the time. They graduated early, investigated radical ideas and movements in the special collections of the college library, and we variously started university while still in high school. Later, in grad school, an equally creative collection of souls poured themselves into performance art projects and shows that were poorly attended but perhaps only because they were so radical and innovative that even the arts community felt at sea with all the new media forms we were inventing.

But there were even more precocious kids in the community. Just before me was Jaron Lanier. I later became good friends with his father when he returned to school in retirement to get his doctorate in psychology (he was a big fan of our performance art shows, of course). But there was also Jeremy Denk whose father drifted around among professorships in the university while also performing in the drama department. Jeremy was a prodigy who excelled in piano and school, ultimately graduating significantly early. He was harassed a bit in school, I think, but that smoothed out as we all got older.

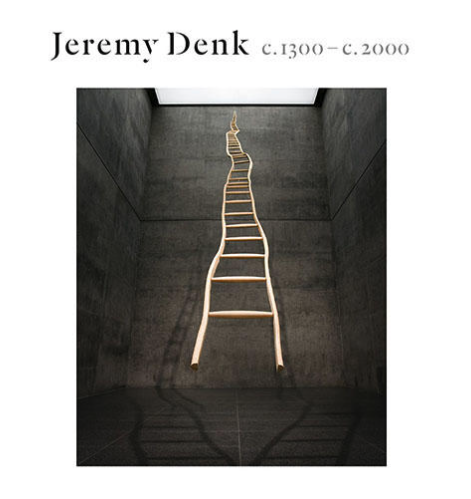

I’ve been tracking Jeremy’s classical piano career for a decade now and his most recent album is one of my favorites. While his 2013 Goldberg Variations was exceptional and the digital download came with fantastic narrative insights into the nature of Bach’s music, Nonesuch Records’ c1300-c2000 is intellectually more ambitious in trying to encapsulate the history of Western music in a single album.

As a pianist, the task was especially daunting. Early music had no pianos, but with deft hands Jeremy renders Medieval and Renaissance songs into pieces that, well, sound almost contemporary. Indeed, he concludes the album with a revisit, not to the opening piece, Doulz Amis, by Guillaume de Machaut, but to the second song by Gilles Binchois, almost completing a cycle near where he began. On the piano, the characteristic trills of voices from Early Music grant a modern, almost jazzy quality to the short songs.

Perhaps even more unexpected was the rapturous joy of Monteverdi‘s Scherzi musicali, which hops along while showing the early signs of baroque verticality. In Denk’s hands it sounds remarkably contemporary with a Django Reinhardt swing to the rhythms.

Time flows forward and all the major figures are represented: Scarlatti and Bach for Baroque; Mozart and Beethoven for Classical; Wagner, Liszt, and Chopin for Romantic; and Brahms like an idiosyncratic return to classical forms with his insistence on absolute music. Denk’s rendition of Liszt’s version of Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde is perhaps my only complaint with the middle section of the album. It is a remarkable story, in a way, that Liszt created a piano version at all given that Wagner was sleeping with Liszt’s daughter Cosima at the time, who was in turn married to Liszt’s protege, but my complaint is only that I really like the orchestrated versions of T&I. The piano tries too hard to create the textures of the orchestra. Piano needs a different kind of music.

I write that fully realizing that by the time we get through the birth of the modern, we return to texture in piano, but it is texture in support of what a piano can do rather than in emulation of an orchestra.

And this is where it gets both challenging and exceptionally interesting. Jeremy pairs Debussy with Schoenberg as we move into the modern. Debussy explores the chromatic in what I view as impressionistic despite Debussy’s own dislike of that descriptor. Meanwhile, Schoenberg completely deconstructs tonality in a way that is largely of academic interest given the overt intellectualism of the work. Later, with Stockhausen and Stravinsky (the uncomposer), it was only natural that there was a persistence of late romanticism as the popular modern classical during that era. Ravel notoriously agreed with public outrage at Bolero, which is even listenable in a colloquial sense of the term, unlike most Schoenberg.

The end game of the album has Philip Glass and György Ligeti, a composer Jeremy has studied in previous albums. Both return to a textural treatment of the piano, with Glass predictable in his minimalism and Ligeti seemingly finding alternative ways to move without movement based on his cluster and micropolyphonic theories of music. A special listening moment is the first note of Glass’s Etude No. 2. The sustain is haunting and it flows between stereo channels until resolving to the center. I assume this credits to the recording engineering and one brilliantly miked piano. I first listened to this in our acoustically alive living room on a Cambridge Audio rig with subwoofer driven by a fine Peachtree Audio amp. I stopped and rolled back the track. Then I turned off the gas fireplace, worrying the curled cats, and did it again. Then I got noise canceling headphones and listened a few more times. For one note.

And we return again to the Renaissance as if Jeremy wanted us to reflect on the journey. Just how different is our music today? If you peel away the effects of instrument changes and advances, from the innovation of the piano, to orchestration itself, and on to Stockhausen’s Musique Concrete, are the changes seemingly circular and less dramatic than we think?

I think back to that now strange landscape of New Mexico with its uniquely multicultural feeling crossed with advanced science and secret military bases and wonder what made it feel so unique, and what drove so many of us kids to dream and excel? Some of my contemporaries claimed it was the lack of distractions afforded by isolation. Others have suggested it was an unexpected aggregation of talented parents who were looking for something new in one of the more distant places in America. Shortly after leaving Microsoft, I even suggested to Alvy Ray Smith that it was the vastness of the landscape that tuned us to expansive thought.

Regardless, I’m astonished by Jeremy’s album and its resonances through time. It is sonically and intellectually as vast as that landscape.