I was once cornered in a bar in Suva, Fiji by an Indian man who wanted to unburden himself and complain a bit. He was convinced that the United States had orchestrated the coups of 1987 in which the ethnically Fijian-dominated military took control of the country. The theory went like this: ethnic Indians had too much power for the Americans to bear as we were losing Subic Bay as a deep water naval base in the South Pacific. Suva was the best, nearest alternative but the Indians, with their cultural and political ties to New Delhi, were too socialist for the Americans. Hence the easy solution was to replace the elected government with a more pro-American authoritarian regime. Yet another Cold War dirty tricks effort, like Mossaddegh or Allende, far enough away that the American people just shrugged our collective shoulders. My drinking friend’s core evidence was an alleged sighting of Oliver North by someone, sometime, chatting with government officials. Ollie was the 4D chess grandmaster of the late 80s.

I was once cornered in a bar in Suva, Fiji by an Indian man who wanted to unburden himself and complain a bit. He was convinced that the United States had orchestrated the coups of 1987 in which the ethnically Fijian-dominated military took control of the country. The theory went like this: ethnic Indians had too much power for the Americans to bear as we were losing Subic Bay as a deep water naval base in the South Pacific. Suva was the best, nearest alternative but the Indians, with their cultural and political ties to New Delhi, were too socialist for the Americans. Hence the easy solution was to replace the elected government with a more pro-American authoritarian regime. Yet another Cold War dirty tricks effort, like Mossaddegh or Allende, far enough away that the American people just shrugged our collective shoulders. My drinking friend’s core evidence was an alleged sighting of Oliver North by someone, sometime, chatting with government officials. Ollie was the 4D chess grandmaster of the late 80s.

It didn’t work out that way, of course, and the coups continued into the 2000s. More amazing still was that the Berlin Wall came down within weeks of that bar meetup and the entire engagement model for world orders slid into a brief decade of deconstruction and confusion. Even the economic dominance of Japan ebbed and dissipated around the same time.

But our collective penchant for conspiracy theories never waned. And with the growth of the internet and then social media, the speed and ease of disseminating fringe and conspiratorial ideas has only increased. In the past week there were a number of news articles about the role of conspiracy theories, from a so-called “QAnon” advocate meeting with Trump to manipulation of the government by Israel’s Black Cube group.

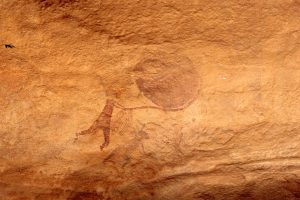

The social and cognitive psychology of conspiracy theories is a topic of recent interest that dovetails with ideas like religious ideation. Believing on faith or on scant evidence applies to both domains, after all. Moreover, the predominant theory that girds both is based on a risk calculation assumed to be left over from early hominid evolution. Here’s how it works. Let’s imagine that we are savannah dwelling porto-humans. We have to eat, drink, mate, and avoid death and the death of our group members in order to thrive. If we hear a rustle in the bush, we need to identify it and whether it represents a risk. And it’s alright if we have false positives but false negatives are deadly. False positives—just seeing or hearing something that isn’t there—has no downside besides general nervousness.

The outcome is part of our extensive set of cognitive biases and takes the name Hypersensitive Agency Detection (HAD). We have a strong tendency to attribute agency to natural phenomena and to misattribute agency to random or temporally-correlated events. The latter is technically the “conjunction fallacy” but it feeds into conspiracy-related thinking. By seeing everything as an intentional agent, even improperly, we reduce our risk. And what about the great swirling metaphysical world behind the veil? That, too, is HAD at work. Conspiratorial thinking also correlates with political conservatism as well as “anomie” or a general distrust of government and feelings of hopelessness.

What overcomes HAD? The obvious one: education level. But our habits about agency are hard to overcome. Even evolutionary biologists have been known to use teleological explanations for traits or behaviors. They don’t think of rams as “having evolved” horns to provide defense or tests of male vigor, but they inadvertently will say so when the better explanation is that the trait arose due to selection. Agency is just built into our language and way of conveying stories. Overcoming conspiracy theories through facts and logic can backfire, too, resulting in a hardening of positions and dismissal of contradictory data.

That our rational faculties are often not terribly rational is no surprise to any of us, but the unique ways in which our biases manifest perhaps should be. Agency detection is key to survival, religion, conspiratorial thinking, and perhaps even schizophrenia, where perceptions are granted external agency. Sometimes I’m impressed we have come so very far as a species, but that may just be a suspicious anomie coloring my perceptions.