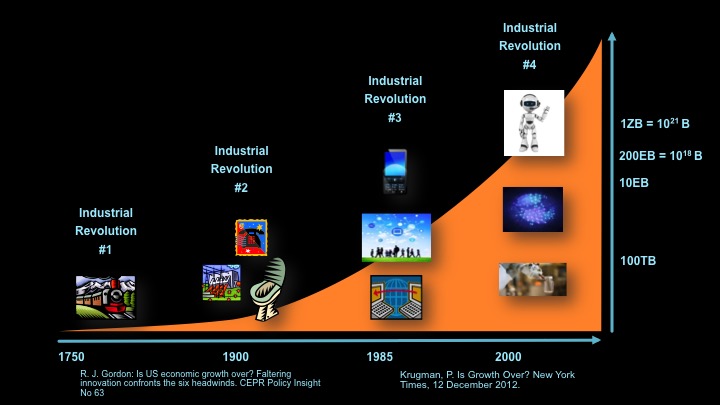

I had some interesting new talking points in my Rock Stars of Big Data talk this week. On the same day, MIT Technology Review published Technology and Inequality by David Rotman that surveys the link between a growing wealth divide and technological change. Part of my motivating argument for Big Data is that intelligent systems are likely the next industrial revolution via Paul Krugman of Nobel Prize and New York Times fame. Krugman builds on Robert Gordon’s analysis of past industrial revolutions that reached some dire conclusions about slowing economic growth in America. The consequences of intelligent systems on everyday life will have enormous impact and will disrupt everything from low-wage workers through to knowledge workers. And how does Big Data lead to that disruption?

I had some interesting new talking points in my Rock Stars of Big Data talk this week. On the same day, MIT Technology Review published Technology and Inequality by David Rotman that surveys the link between a growing wealth divide and technological change. Part of my motivating argument for Big Data is that intelligent systems are likely the next industrial revolution via Paul Krugman of Nobel Prize and New York Times fame. Krugman builds on Robert Gordon’s analysis of past industrial revolutions that reached some dire conclusions about slowing economic growth in America. The consequences of intelligent systems on everyday life will have enormous impact and will disrupt everything from low-wage workers through to knowledge workers. And how does Big Data lead to that disruption?

Krugman’s optimism was built on the presumption that the brittleness of intelligent systems so far can be overcome by more and more data. There are some examples where we are seeing incremental improvements due to data volumes. For instance, having larger sample corpora to use for modeling spoken language enhances automatic speech recognition. Google Translate builds on work that I had the privilege to be involved with in the 1990s that used “parallel texts” (essentially line-by-line translations) to build automatic translation systems based on phrasal lookup. The more examples of how things are translated, the better the system gets. But what else improves with Big Data? Maybe instrumenting many cars and crowdsourcing driving behaviors through city streets would provide the best data-driven approach to self-driving cars. Maybe instrumenting individuals will help us overcome some of things we do effortlessly that are strangely difficult to automate like folding towels and understanding complex visual scenes.

But regardless of the methods, the consequences need to be considered. Our current fascination with Big Data may not lead to Industrial Revolution 4 in five years or twenty, but unless there is some magical barrier that we are not aware of, IR4 seems to be inevitable. And the impacts will perhaps be more profound than the past revolutions because, unlike those transitions, the direct displacement of workers is a key component of the IR4 plan. In Rotman’s article, Thomas Piketty’s r > g is invoked to explain the excess return on capital (r) versus economic growth rate (g) and how that leads to a concentration of wealth among the richest members of our society, creating a barbell distribution of economic opportunities where the middle class has been dismantled due to (per Gordon) the equalization of labor costs through outsourcing to low-cost nations. But at least there remains a left bell to that barbell in that it is largely impossible to eliminate the services jobs that are critical to retail, restaurant, logistics, health care, and a raft of other economic sectors.

All that changes in IR4 and the barbell turns into the hammer from the Olympic hammer throw as the owners of the capital take over the entire cost structure for a huge range of economic activities. The middle may not initially be gone, however, as maintenance of the machinery will require a skilled workforce. Even this will be a point of Big Data optimization, however, as predictive maintenance and self-healing systems optimize against their failure modes over usage cycles.

So let’s go back to Gordon’s pessimism (economics is, after all, the “dismal science”). What headwinds and tailwinds are left in IR4? Perhaps the most cogent is the recommended use of redistributive methods for accelerating educational opportunities while reducing the debt load of American students. The other areas that are discussed include unlimited immigration to try to offset hours per capita declines due to retirement and demographic effects, but Gordon’s application of this is not necessarily valid in IR4 where low-skilled immigration would cease because of a lack of economic opportunities and even higher-skilled workers might find themselves displaced.

One lesson learned from past industrial revolutions is that they created more opportunities than worker displacements. Steam power displaced animal labor and the workers needed to shoe and train and feed those animals. Diesel trains displaced steam engine builders and mechanics. Cars and aircraft displaced trains. But in each case there were new jobs that accompanied the shift. We might be equally optimistic about IR4, speculating about robot trainers and knowledge engineers, massive extraction industries and materials production, or enhanced creative and entertainment systems like Michael Crichton’s dystopian Westworld of the early 70s. Is this enough to buffer against the headwind of the loss of the service sector? Perhaps, but it will not come without enormous global disruption.