When I say that “greed is not good” the everyday mind creates a series of images and references, from Gordon Gekko’s inverse proposition to general feelings about inequality and our complex motivations as people. There is a network of feelings and, perhaps, some facts that might be recalled or searched for to justify the position. As a moral claim, though, it might most easily be considered connotative rather than cognitive in that it suggests a collection of secondary emotional expressions and networks of ideas that support or deny it.

When I say that “greed is not good” the everyday mind creates a series of images and references, from Gordon Gekko’s inverse proposition to general feelings about inequality and our complex motivations as people. There is a network of feelings and, perhaps, some facts that might be recalled or searched for to justify the position. As a moral claim, though, it might most easily be considered connotative rather than cognitive in that it suggests a collection of secondary emotional expressions and networks of ideas that support or deny it.

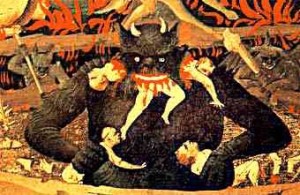

I mention this (and the theories that are consonant with this kind of reasoning are called non-cognitivist and, variously, emotive and expressive), because there is a very real tendency to reduce moral ideas to objective versus subjective, especially in atheist-theist debates. I recently watched one such debate between Matt Dillahunty and an orthodox priest where the standard litany revolved around claims about objectivity versus subjectivity of truth. Objectivity of truth is often portrayed as something like, “without God there is no basis for morality. God provides moral absolutes. Therefore atheists are immoral.” The atheists inevitably reply that the scriptural God is a horrific demon who slaughters His creation and condones slavery and other ideas that are morally repugnant to the modern mind. And then the religious descend into what might be called “advanced apologetics” that try to diminish, contextualize, or dismiss such objections.

But we are fairly certain regardless of the tradition that there are inevitable nuances to any kind of moral structure. Thou shalt not kill gets revised to thou shalt not murder. So we have to parse manslaughter in pursuit of a greater good against any rules-based approach to such a simplistic commandment.… Read the rest