Paul Vitanyi has been a deep advocate for Kolmogorov complexity for many years. His book with Ming Li, An Introduction to Kolmogorov Complexity and Its Applications, remains on my book shelf (and was a bit of an investment in grad school).

Paul Vitanyi has been a deep advocate for Kolmogorov complexity for many years. His book with Ming Li, An Introduction to Kolmogorov Complexity and Its Applications, remains on my book shelf (and was a bit of an investment in grad school).

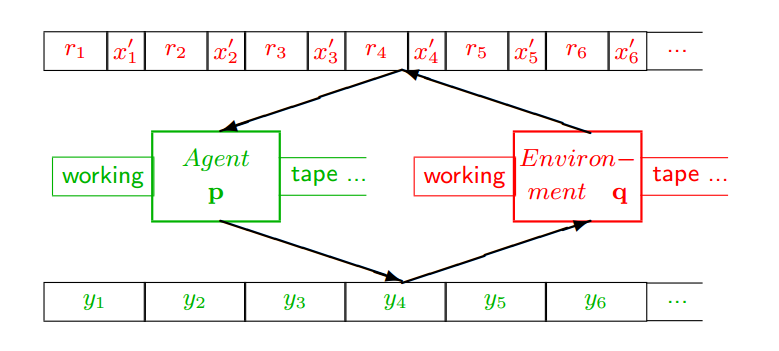

I came across a rather interesting paper by Vitanyi with Rudi Cilibrasi called “Clustering by Compression” that illustrates perhaps more easily and clearly than almost any other recent work the tight connections between meaning, repetition, and informational structure. Rather than describing the paper, however, I wanted to conduct an experiment that demonstrates their results. To do this, I asked the question: are the writings of Dante more similar to other writings of Dante than to Thackeray? And is the same true of Thackeray relative to Dante?

Now, we could pursue these questions at many different levels. We might ask scholars, well-versed in the works of each, to compare and contrast the two authors. They might invoke cultural factors, the memes of their respective eras, and their writing styles. Ultimately, though, the scholars would have to get down to some textual analysis, looking at the words on the page. And in so doing, they would draw distinctions by lifting features of the text, comparing and contrasting grammatical choices, word choices, and other basic elements of the prose and poetry on the page. We might very well be able to take parts of the knowledge of those experts and distill it into some kind of a logical procedure or algorithm that would parse the texts and draw distinctions based on the distributions of words and other structural cues. If asked, we might say that a similar method might work for the so-called language of life, DNA, but that it would require a different kind of background knowledge to build the analysis, much less create an algorithm to perform the same task.… Read the rest

The impossibility of the Chinese Room has implications across the board for understanding what meaning means. Mark Walker’s paper “

The impossibility of the Chinese Room has implications across the board for understanding what meaning means. Mark Walker’s paper “