There is, necessarily, an empty center to secular existence. Empty in the sense that there is no absolute answer to the complexities of human life, alone or as part of the great societies that we have created. This opens us to wild, adventurous circuits through pain, meaning, suffering, growth, and love. Religious writers in recent years have had a tendentious tendency to denigrate this fantastic adventure, as Andrew Sullivan does in New York magazine. The worst possible argument is that everything is religion insofar as we believe passionately about its value. It’s wrong if for no other reason than the position of John Gray that Sullivan quotes:

There is, necessarily, an empty center to secular existence. Empty in the sense that there is no absolute answer to the complexities of human life, alone or as part of the great societies that we have created. This opens us to wild, adventurous circuits through pain, meaning, suffering, growth, and love. Religious writers in recent years have had a tendentious tendency to denigrate this fantastic adventure, as Andrew Sullivan does in New York magazine. The worst possible argument is that everything is religion insofar as we believe passionately about its value. It’s wrong if for no other reason than the position of John Gray that Sullivan quotes:

Religion is an attempt to find meaning in events, not a theory that tries to explain the universe.

Many religious people absolutely disagree with that characterization and demand an entire metaphysical cosmos of spiritual entities and corresponding goals. Abstracting religion to a symbolic labeling system for prediction and explanation robs religion, as well as reason, art, emotion, conversation, and logic, of any independent meaning at all. So Sullivan and Gray are so catholic in their semantics that the words can be replanted to justify almost anything. Moreover, the subsequent claim about religion existing because of our awareness of our own mortality is not borne out by the range of concepts that are properly considered religious.

In social change Sullivan sees a grasping towards redemption, whether in the Marxist-idolatrous left or the covertly idolatrous right, but a more careful reading of history proves Sullivan wrong on the surface, at least, if not in the deeper prescription. For instance, it is not faith in progress that has been part of the liberal social experiment since the Enlightenment, but a grasping towards actual reasons and justifications for what is desired and how to achieve it. Contra Sullivan, Steven Pinker is not a religious writer at all in his carefully drawn conclusions about our elimination of poverty and reduction in all the horrors we have suffered as human beings. He is doing what the religious never have done: using rationality to identify how to achieve well-being at a scale that has never existed before. And reading out the statistics that show progress.

That disjunction in how religious versus secular thinking operates is nowhere highlighted better than in the proactive humanism of the effective altruism movement. In effective altruism, these same tools of reason are applied directly to the goal of maximizing improvement to continue to accelerate the diminishment of suffering throughout the world. This is not saving souls at the tip of a sword, just handing out mosquito netting.

Are these movements ultimately the product of Christian ideas about individuality and progress, as per Sullivan? The intellectual histories that we have for comparison are unfortunately smeared out by the fact that our modern world grew up in the most recent Christian-infused milieu. You could also claim, with a concomitant lack of anything beyond speculative theorization, that had Western Empire not declined due to Christian influences, positive social change would have come sooner and without the period of Dark Ages negation that had a fixed and scholastic social order. Gibbon did. Did Christianity have a moderating influence on American politics in the past? Also hard to say since it was also applied to justify slavery, to dehumanize indigenous peoples, to minimize civil rights for women and minorities, and, yes, to also press for abolition and change when the scriptural readings so moved the people.

I’m always amazed at how religious writers arrogate a whiff of special truth from their swelling breasts. In the mad flight from the terror of unknowing, the secular and the humanist are driven by all the great achievements that surround us. Our son, around 11, once asked what I thought was the greatest scientific achievement of the human race. He was very surprised by my suggestion that the germ theory of disease had to be among the greatest. We went from believing that spirits and unknowables governed life and death to the realization that we are part of a biological continuum and, in due course, that our seats of reason are even subject to knowing.

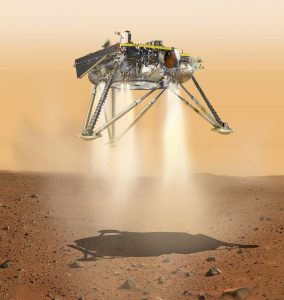

Whether it is reductions in suffering through reasoned action, the landing of robotic explorers on Mars, the creation of a society that exalts freedom as a social good, or the deconstruction of ideas of art and music, the secularist can see this unfolding reality as an incredible accomplishment that fills the soul with transcendent joy, not of some alien creator from long ago, but of our own capacity to become.

And so let there be poetics for the upcoming solstice. Let the knowledge of the music of the spheres, in our detailed reckonings of the precise motions of these fleet worlds, become a flame, and then an inferno, and then consume your whole being, that you can stand at the precipice of what you can become, and sing out against the travails of life that you are mortal and a machine of guts and blood and honor and love, and do something new and incredible that makes us more than mere sheep, that makes us, in our endless becoming, the realized possible.

See also, Richard Carrier’s analysis of Tom Holland’s article. Dr. Carrier goes into considerable more detail on the historical flaws of claiming special status for Christianity in history.

The problem I have mostly with humanism is that it proposes that humans, using this tool of reason, can solve all of our own problems. I think this leads to the temptation that any particular individual or group possesses that solution – and anyone else who doesn’t is wrong. This can lead to conflict – after all: “I’m right and reasonable – you’re wrong and an idiot” (but that’s what everyone thinks).

One thing I’ve always appreciated about religion is that it seems to be the one, single counterforce that suggests to humanity: “No – you don’t know everything.” If you think you know everything, well – so does the other person – and you’ll probably fight to prove it.

I think this is why all spirituality contains some form of deference, humility, subordination and respect for things working in mysterious ways. (Admittedly, religion as an institution has almost universally and invariably failed to follow this, often claiming there is “only one right way” and they know it.)

If you take this deference to the unknown out of the equation, well then you’re left with humans (hence: humanism). In other words, a bunch of people who are sure the entire world is explainable, and there’s no point in deferring to anyone, since we can just use reason to smite our opponents, and then they will smite back, but that’s okay.

My point of all this is that humanism seems to put the solution to everything squarely in the hands of humans, and I’m not sure that’s the best place to put it. I think, with just enough overconfidence, we may even destroy ourselves.

I’d be curious to hear your thoughts on this – I’ve only developed this personal theory somewhat recently.

Absolutely. That’s the entire spirit of the enlightenment (and it’s critique). The critical developments on the secular side are balances of power, peer review, meritocracy, democratic processes, policy analysis, and so on. If those mechanisms don’t seed proper humility in the face of uncertainty (when paired with examples), I’m not sure how spirituality can do anything different?

The diversity of opinions in humanism and, broadly, secular governance is something like the diversity of opinions in religious circles that range from “kill all unbelievers” and ‘the earth must be flat and fitted with a metal firmament” to essentially humanistic concerns for the poor.

Secularism just operates with a recognition that tradition and received wisdom is not necessarily perfect and may be deleterious or counter to human thriving.

Yes, good point that humanism is an overly broad term nowadays. And I particularly agree with this: “If those mechanisms don’t seed proper humility in the face of uncertainty (when paired with examples), I’m not sure how spirituality can do anything different”

I do like how secularism has slipped in “luck” to explain the unknown. Everyone now seems to defer to lucky genes or lucky parents or lucky events in life. It seems this has the same benefits of admitting you don’t know everything, while not chalking it up to something which has no evidence (though I think they get at the same thing, which is the unknown and unknowable).