When I was eight or nine, I traveled with my father up into the rarefied air of the Sacramento Mountains of Southern New Mexico. Getting there was long, hot and complicated. Our VW van pushed up over the mountain passes as thunderheads rolled in from the west, plum and steel-gray, and the sky flashed and shuddered under the monsoonal effects of the late-summer deserts. I avoided touching the metal surfaces of the VW van as my father, a professor of electrical engineering, explained how the lighting, were it to hit the car, would likely melt the tires and travel through the shell of the van and into the ground below.

When I was eight or nine, I traveled with my father up into the rarefied air of the Sacramento Mountains of Southern New Mexico. Getting there was long, hot and complicated. Our VW van pushed up over the mountain passes as thunderheads rolled in from the west, plum and steel-gray, and the sky flashed and shuddered under the monsoonal effects of the late-summer deserts. I avoided touching the metal surfaces of the VW van as my father, a professor of electrical engineering, explained how the lighting, were it to hit the car, would likely melt the tires and travel through the shell of the van and into the ground below.

We were in search of another kind of lightning, however, as we passed through the Border Patrol check-point near White Sands and ascended into the Ponderosa Pines of the high, western mountains. The van chugged along but kept ascending and any limitations it may have had were lost on my youthful mind as the smell of pine needles and the cooler air rolled in through the open windows until we finally slowed to a crunching stop in a gravel lot near a couple of unimpressive shacks. We were above the clouds, with just the tops of the cumulonimbus visible to the south and west.

I knew that I was at a place called Sunspot and that there were telescopes there that were used to look at the sun. It was an act of technological disregard of the countless warnings I had received about looking at the sun as a child, including when my father brought home dense smoked filters from the Naval Observatory in Washington DC when I was four to let us watch a full solar eclipse. Yet, here at Sunspot, hidden among the shacks was a telescope that monitored the sun’s surface by day, defying the limitations of the human eye through reflections, filters, and care.

We wandered a bit among the buildings and then entered one with a simple cement floor. A few cobwebs hung in the corners of the unfinished and uninsulated shed-like structure. And there was the object of his interest: a plain cube of plywood around two feet on a side with wires emerging from it. There was no open sky or blazing trail of sunlight poking down through a tube into a hot, boiling reactor. It was inside a closed building.

I was given an explanation that day, but didn’t really understand what the device was until around my junior year in college during a particle physics course. Simply put, it was a cosmic ray observatory that consisted of a sandwich of charged metal plates with plastic between them. When cosmic rays hit the plates they would, with regularity, impact atoms and transfer their energy by dislodging electrons. Because the plates had a potential difference between them, little lightning bolts would erupt between the plates and the emitted light would trigger a camera to take a picture. I suspect the camera was a film camera, but it might have been video or something more exotic.

I remembered that visit to Apache Point while reading a paper on my iPad in Boulder Colorado two days ago. I was in Denver for a conference on defense intelligence issues and wandered up to Boulder for dinner. The paper I was reading was about the ongoing efforts to understand “Dark Energy,” a hypothesized energy that pervades the universe and can be used to account for the observed accelerating expansion of the universe. And, frankly, no one really understands this. It could be that physics is really wrong. It could be that physics is partly wrong but only at very large scales. It could be that the vacuum of empty space is energetic and productive at the quantum level. I had gone to Boulder because my father had done a postdoc there briefly prior to moving on the Naval Observatory and I had vague, snowy memories of the place and wanted to revisit.

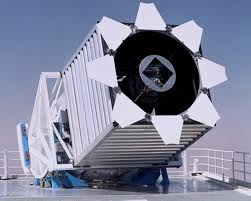

Moreover, connecting the threads together is that the current efforts to understand this expanding universe are centered on a sky survey in infrared being conducted at Apache Point. The telescopes and cameras are extremely sophisticated compared with the stack of steel plates that were so unremarkable in my childhood memories, but the goal remains to understand the universe in all its magical details.

After finishing the article over an IPA paired with an elk burger and sweet potato fries, I read Neil deGrasse Tyson’s article in Foreign Affairs on The Case for Space.