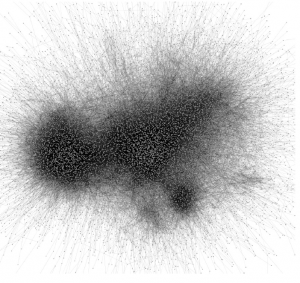

Edward Snowden set off a maelstrom with his revelation concerning the covert use of phone records and possibly a greater range of information. For those of us in the Big Data technology universe, the technologies and algorithms involved are utterly prosaic: given the target of an investigation who is under scrutiny after court review, just query their known associates via a database of phone records. Slightly more interesting is to spread out in that connectivity network and identify associates of associates, or associates of associates who share common features. Still, it is a matching problem over small neighborhoods in large graphs, and that ain’t hard.

Edward Snowden set off a maelstrom with his revelation concerning the covert use of phone records and possibly a greater range of information. For those of us in the Big Data technology universe, the technologies and algorithms involved are utterly prosaic: given the target of an investigation who is under scrutiny after court review, just query their known associates via a database of phone records. Slightly more interesting is to spread out in that connectivity network and identify associates of associates, or associates of associates who share common features. Still, it is a matching problem over small neighborhoods in large graphs, and that ain’t hard.

The technological simplicity of the system is not really at issue, though, other than to note that just as information wants to be free—and technology makes that easier than ever—private information seems to be increasingly easy to acquire, distribute, and mine. But let’s consider a policy fix to at least one of the ethical dilemmas that is posed by what Snowden revealed. We might characterize this by saying that the large-scale, covert acquisition and mining of citizen data by the US government violates the Fourth Amendment. Specifically, going back in the jurisprudence a bit, when we expect privacy and when there is no probable cause to violate that privacy, then the acquisition of that information violates our rights under the Fourth. That is the common meme that is floating around concerning Snowden’s revelations, though it is at odds with widespread sentiment that we may need to give up some rights of privacy to help fight terrorism.

I’m not going to argue here about the correctness of these contending constructs, however. Nor will I address the issue of whether Snowden should have faced the music, fled, or whether he simply violated a rule and an oath requiring secrecy.… Read the rest